Last month we had the pleasure of attending the inaugural Festival Kampung Buntoi (Buntoi Village Festival). We travelled there in company with Pak Wondo, his wife Ibu Tata and son Andi. Buntoi is Ibu Tata’s home village, and we stayed at the home of her aunt and uncle.

We were only there for two days of the 3-day festival, but we had a great time. We had many interesting encounters and experiences (as we always seem to do), and saw some impressive and unique dance, music and theatre performances. Some of the outrageous costumes (such as these ones worn by dancers from the Sanggar Marajaki group ) alone were worth the journey.

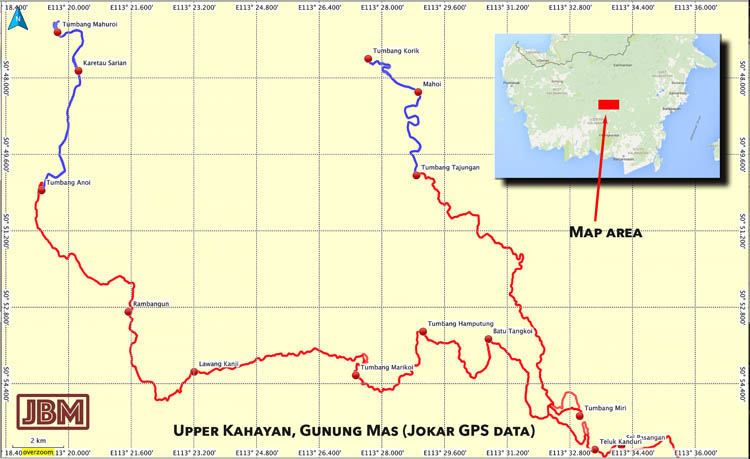

Buntoi is a village of 2,500 people,attractively located on the banks of the Kahayan River, about two and a half hours downstream from where we were living at Sei Gohong (on the Rungan River). The Kahayan is a big wide river down there, and although Buntoi is just across the river from the district capital of Pulang Pisau, it takes nearly an hour to get there by road.

It was apparently founded around 1670, Buntoi used to be known as Petak Bahandang (meaning ‘Red Earth’). This former name came from the story about a raiding party of headhunters who were all killed by makhluk gaib (supernatural creatures protecting the village). According to the story, the villagers awoke to find the ground stained red with the blood of the would-be attackers.

The economy is based around fishing and rubber plantations, which seem to be thriving in this area in spite of the current low price of latex rubber. There are also a number of tall buildings like the one above, constructed to house the swiflets known as burung walet (Aerodramus fuciphagus). These are the birds responsible for producing the highly valuable edible birds nests. Recordings of the birds’ call are played continuously to attract them to the building.

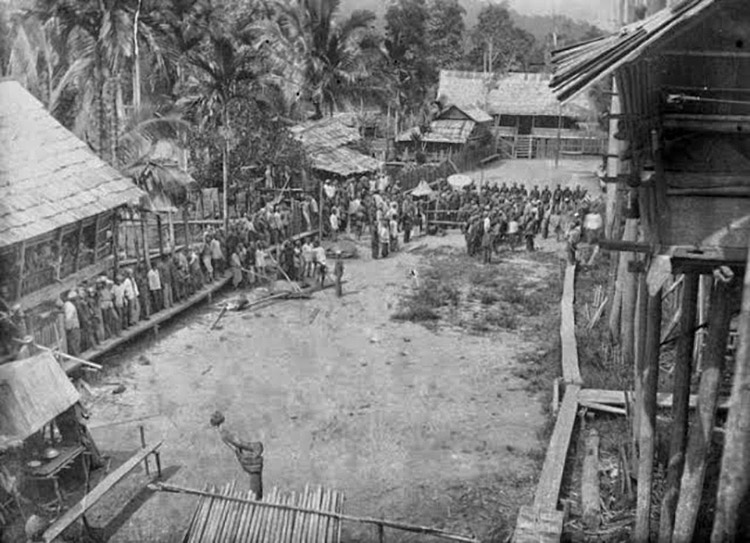

Like all good festivals, Festival Kampung Buntoi began with a spectacular street parade, along the length of the road beside the river (which is pretty much the only road in town) and on to the festival venue. There were marching bands, people in splendid and ornate traditional Dayak costumes, event organisers and local dignitaries, and many children of the village.

The road was lined with… well Karen and I were just about the only cheering well-wishers. It WAS a treat.

There was an interesting and eclectic mixture of the traditional and the contemporary in the style in the parade participants – a blending which was to continue throughout the Festival performances.

This is great to see; Kalimantan cannot be a ‘cultural theme park’, frozen in some imagined long-gone age. The wonderful traditional warrior costumes on display at the Festival performances, are now only worn for performances, and young Dayak men can commonly be seen wearing Manchester United jerseys – but never bark vests… In fact many of these performance costumes are very contemporary reinterpretations of ‘traditional’ attire, unlike anything you can find in old photographs. They look great in photographs, but they owe more to the here-and-now than to history, and perhaps owe more to Carnivale than to Kalimantan.

The venue for the many performances of the Festival was the Rumah bambu (‘Bamboo House’), built in 2012 as a meeting hall and events venue with funding from the UNDP as part of the REDD+ (‘ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation’) project. It was opened by the then Governor of Kalimantan Tengah in September 2013 as the Pusat Sarana Komunikasi Iklim (the ‘Climate Communications Facilitation Centre’).

As the only foreigners in attendance, we were (as always!) subject to a lot of (friendly) attention, and innumerable photo requests. Here’s Karen posing with event officials (that’s Pak Turai S. Deken – ‘Ko-ordinator Panitia‘ on the right) and local police officers.

Several temporary warung (foodstalls) were set up under a marquee in the field adjacent to the Festival building. We enjoyed several delicious meals there – including chicken curry, sweet and sour catfish, and chicken soup. (Note the traditional costumes worn by the local Dayak people).

The two MC’s (Chandra Intan Hakim and Ananta Nurudi Sawung) were really good – funny, relaxed, and able to ad lib freely to seamlessly fill in the gaps between the performers. At one point they called up a couple of bules (i.e. Karen and I) from the audience to talk about their impressions of the festival. We had not long arrived, so we didn’t have much to say! It was little awkward.

Intan is from Jakarta, and she has a wonderfully colourful and zany dress sense – which matches her ebullient personality. When he’s not compering festivals, Ananta is a freelance photographer who lives in Palangka Raya.

On the morning we arrived in Buntoi, we got to the performance area just as this young dance troupe (the Sanggar Palampang Tarung) were finishing, so unfortunately we didn’t get to see them perform. But they kindly agreed to pose for some photos for us.

Along with the music, dance and theatre there were also some interesting talks and Q&A sessions, on (extremely!) diverse topics. It was frustrating for us that we understood just enough to be very interested, but too little to fully comprehend what was being said by the accomplished and articulate speakers.

Dr Andang Bachtiar (l) is a geologist, former President of the Indonesian Geologists Association, and currently a member of the National Energy Council of Indonesia. He spoke about the historical and cultural implications of the geomorphology of Kalimantan and the Indonesian archipelago.

Rayhan Sudrajat (c) was largely responsible for initiating the whole Buntoi Festival, harnessing community spirit and working cooperatively with local people to make it happen. He is a both a musician and an ethnomusicologist, with wide-ranging interests (including linguistics, psychology, culture and philosophy). His eclectic musical interests range from traditional Sundanese music to the Beatles. Based in the Bandung (Java), he also operates a recording studio.

Didik Nini Thowok (r) is a dancer, mime artist, choreographer and teacher whose international career has developed the Indonesian tradition of cross-gender dance performances. His every move confirms him as a dancer – fluid, elegantly controlled gestures, no unnecessary moves. He spoke about his personal history, traditions of cross-gender dance in various other cultures – and the art of stage make-up!

Zulfikar Muhammad Nugroho has lived in various parts of East Java and Kalimantan, and now lives in Palangka Raya, where he has been a student at the Universitas Muhammadiyah.

He’s an expert player of the sape (usually called kecapi in Central Kalimantan). The sape (pronounced ’saa-pay’) can have anywhere from 2 – 5 strings, with all but the upper string usually just strummed as a harmonic drone. It may have no frets, three or many frets, and may be quite compact or up to a metre or more long. In summary, it’s form varies! But it should always be carved from a single piece of wood, with the back usually hollowed-out.

Performance sponsored by the Yayasan Permakultur Kalimantan, with Ahmad Fullah at centre stage. Their performance was about the Dayak fire management practice known as Milang Seha. Noor Julaiha was the Creative Director.

Sanggar Tingang Panunjung Tarung.

BellacoustiC Indonesia are a Palangka Raya musical group, whose goal is “creativity in music which aims to promote the customs and culture”. They certainly achieved that in their all-too-short set at Buntoi. Each one of them is a virtuoso.

Theo Nugraha performed two sets at the Festival, one solo and one with Rayhan Sudrajat (he does a lot of collaborations in his work).

He describes himself as a ‘Noise / Experimental Soundartist from Borneo’ (he’s based in Palangka Raya and Samarinda). The Village Voice reviewed one of his recordings, and described him as a ‘noise evangelist’. It’s certainly experimental sound, some of it ethereal and ambient Eno-esque, some of it collections of environmental sounds recorded in the field, and some of it a relentless grinding wall-of-noise-and-static.

A performer from Sanggar Betang Batarung, Palangka Raya.

Dancers from the wonderful Sanggar Riak Renteng Tingang, Palangka Raya

Bukung character from the Komunitas Teater Palangka Raya

Performers of the Sanggar Marajaki

Redy Eko Prastyo is a prominent musician and composer, based in Malang (Java), but he performs extensively across Indonesia (and in Europe). HIs musical style spans traditional Indonesian and jazz styles, and a fusion of the two. At Buntoi he was playing a unique, handmade electric ‘sape’. The sound, and the quality of musicianship, was lovely.

Trie Utami Sari is a very well known singer and songwriter from Bandung. Her fame with Indonesian audiences is the result of several hit recordings (as well as five albums), and for appearing as a judge on the popular TV talent show Indosiar Fantasy Academy. Her voice (seen here improvising over music of BellacoustiC) is gorgeous.

The final set on Saturday night was a something of a collaborative jam session, with a number of musicians and dancers on stage together. The music reached a crescendo full of soulful energy and warmth. It was a fitting end to wonderful series of performances.

Apart from the Rumah Bambu, Buntoi village also has another (and much older) significant building – the Rumah Adat (Traditional house).

The house was built between 1867-70 by Singa Jala, with materials (mostly kayu ulin timber) brought from Manen Paduran, which is (a long way) further upstream on the Kahayan River. Being made from ironwood, it is a very sturdy structure, but it has also benefited from some restoration work in recent years – such as new shingles for the roof. Some parts, including the rooms for the four slave families who used to live there, are no longer standing.

The current head of the family, who is a direct descendant of Singa Jala, talked to us about the history of the house, including its role as a centre of the nationalist forces during the struggle for independence from the Dutch after 1945.

Inside the betang is a fine set of gongs, and a tiny (and damaged) bronze cannon (just visible on the right of the photo above).

There are also some very nice balanga, Chinese-made ceramic jars, which are valued and treated as family heirlooms by Dayak families in Kalimantan. There were also brass spittoons (known as peludahan), brass bowls (bokor, or sangku in Bahasa Dayak Ngaju), and some old baskets made of rotan (rattan).

We also were entertained by one quite unexpected performance. During a lull in the Festival programme, we went for a drive with Wondo, Tata and Andi further south to the village of Kanamit Barat. To our surprise, there was a wedding ceremony under way at which a Kuda Lumping troupe were performing (as we have previously seen in Java at Prambanan, and in Kalimantan at Suka Mulya village in 2014 and 2015).

And just when we were marvelling at having chanced upon this ancient, mysterious and powerful Javanese trance performance in a remote(-ish) village of Central Kalimantan, a woman (Mbak Muvida) comes up to us to say that she used to work at YUM (where I was volunteering), and that she recognised us from photos on a friend’s Facebook page. Welcome back to 2016…

There’s a great short (9 minute) video on YouTube which gives a really good feel for the Festival Kampung Buntoi – and it contains samples of the wonderful dance and music performances. (It even includes a couple of quick glimpses of the bules-in-residence – see if you can spot us!)

Our thanks go out to the friendly and hospitable people of Buntoi village; to the visionary and meticulous organisers of the Festival; and of course to the creative and hugely talented performers who attended. May your talents be rewarded with career success. Special thanks to Rayhan Sudrajat for helping me identify performers in some of the photos – but any residual errors are my responsibility!)

We left with two sincere hopes: that the inaugural Festival Kampung Buntoi may be just the first in a long and successful series of Buntoi Festivals – and that we may have the good fortune to attend again….