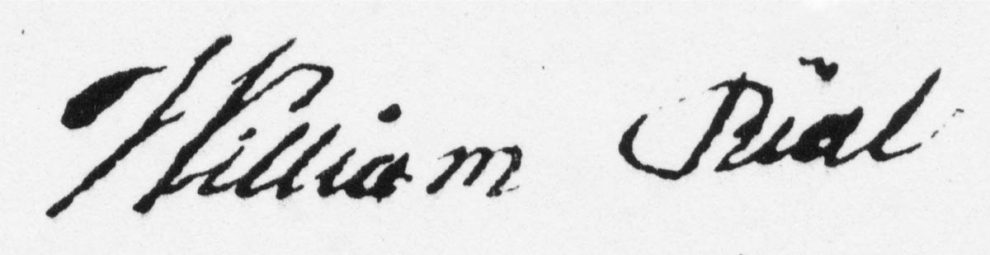

“If there is any one thing more indispensably necessary than another in an article intended to meet the public eye, it is accuracy, or to speak more plainly, truth.” (William Rial, 1861)

I believe this to be a photo – most likely the only photo – of my great-grandfather, William Rial. He died in 1867, so it’s remarkable that the picture even exists, and has survived to this day.

I treasure it.

It’s a grainy image, scratched and sepia-toned with age. William looks down at us, standing on top of a log (or a rock?), in his buttoned-up waistcoat and neat bow tie. In his younger years he was described as having a “dark, ruddy and freckled” complexion, hazel eyes and brown hair. His lower front teeth were “irregular”, and he had two prominent scars – one on the left side of his mouth, and one (perhaps visible in the photograph?) on the back of his right thumb. He stood 5’ 7” tall.

He looks relaxed and composed, but now, 160 years later, he is inscrutable. What I would give to know his thoughts as he posed for the picture – and what stories he might tell his unimagined great-grandson about his extraordinary life!

His story, and those of the many larger-than-life characters who figured in it, is a colourful narrative of 19th-century colonial life in New South Wales. There’s plenty of high drama: crimes and punishments, great ambitions and bankruptcies, romances and violent conflicts. And at least four deaths by gunshot along the way…

Early years

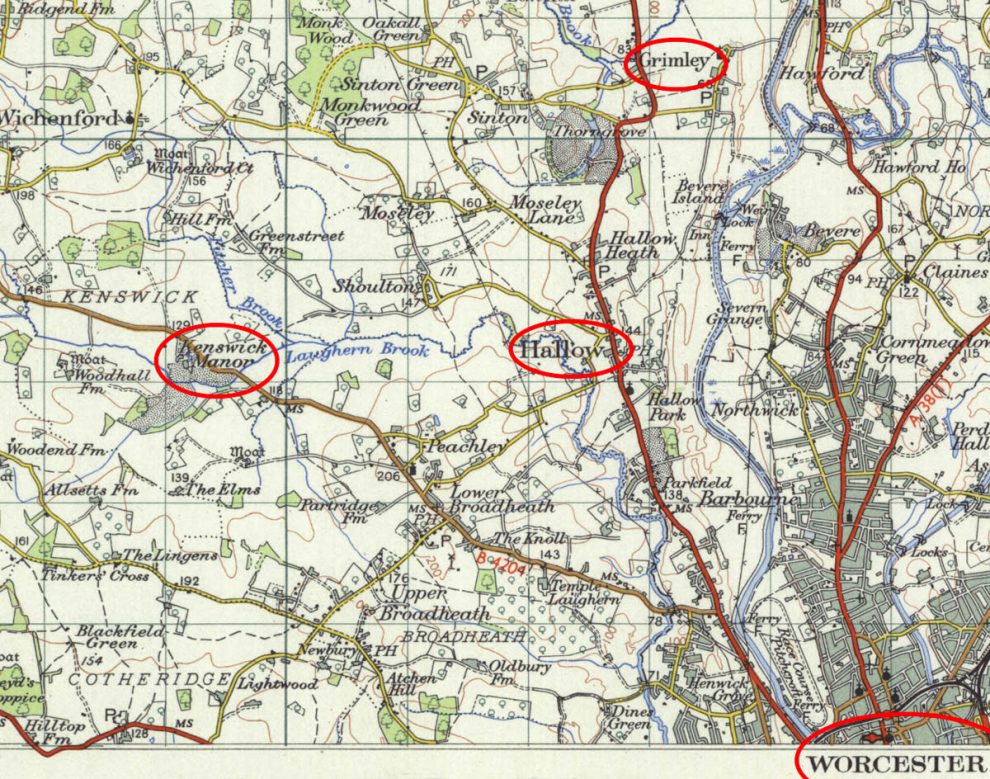

As far as we can tell from the scant records, William Rial’s early years were unremarkable. He was born in 1807 or 1808, in the village of Hallow, Worcestershire, a few kilometres northwest of Worcester city, the fifth (and youngest) child of Edward and Mary. His family had lived in Worcestershire for generations, and it’s likely that there was some historic connection to the village of Ryall, (‘Ruyhale’, ‘Ryhal’, ‘Rehale’, ‘Royall’ ‘Ryolles Court’) in the south of Worcestershire.

None of William’s family appears to have been fully literate, which partly explains why their family name shows in the records at various times as ‘Ryall’, ‘Royal’, ‘Riall’ or ‘Rial’. They were working poor, and young William (who in his youth could read but not write) found employment nearby as a farm labourer at Kenswick, a former manorial estate dating from the 13th Century.

He married a local woman, Sarah Brown, and by the time their first child John (Ryall) was born in 1831, they were residents of Grimley (about 2km north of his birthplace in Hallow). Their second son (also named William) was christened at the church in Grimley on 23 March 1834. But shortly after this happy event, William’s fortunes were to change radically – and permanently.

The Great Grog Robbery

Two weeks after the christening, on 7 April, William appeared in court (the ‘Worcestershire Easter Sessions’), charged on two counts of robbery from his master, one Thomas Horton of Kenswick. Beside him in the dock were three of his fellow workers from Kenswick: Richard Mansell (aged 31), John Pitcher (30) and William Beavan (20). It was alleged that, on the 15th of March, and again on the 22nd March (the day before his son’s christening), the four accused had ‘plugged’ two hogsheads of apple cider and perry from Horton’s cellar, stealing a total of four gallons of grog. (‘Perry’ is a cider-like liquor made from fermentation of certain pear varieties. It was a popular tipple at the time, particularly in the ‘Three Counties’ of Worcestershire, Gloucestershire and Herefordshire.)

The formal indictment was read out to the Court. It made it clear that this was no trivial offence, declaring that the accused,

“with force of arms at [Kenswick] two gallons of Cyder of the value of one shilling and two gallons of Perry to the value one shilling of the goods and chattels of the said Thomas Horton their Master as aforesaid then and there being found feloniously did steal and take and carry away against the form of the Statute in such case made and provided against the peace of our Lord the King, his Crown and Dignity”.

Don’t offend the King’s Dignity. The court proceedings were reported in some detail by the local newspapers. Mansell was considered to be the ringleader of the robbery, as he was a trusted employee who carried a skeleton key giving him access to all locks at Kenswick. Even the prosecutor (Horton) considered that Rial had been “drawn into the affair”, and a number of witnesses attested to the good character of the accused.

The chief witness for the prosecution was Catherine Binnersley, a 16-year-old servant at Kenswick. (Interestingly, her sister, who also worked at Kenswick, was “under a promise of marriage” to one of the accused – most likely the youngster William Beavan).

Catherine claimed that she had seen the four men take the cider. However her credibility was severely challenged by Mr Godson, representing the prisoners. He noted that she had previously made allegations of attempted rape and theft of butter against other men, and he even called in her mother to testify that she wouldn’t believe anything Catherine said – even if declared under oath.

After the presentation of all evidence had concluded, the jury deliberated at length. They seemed unable to reach a verdict, with one juror in particular disbelieving Catherine’s evidence. To speed things up, the Chairman of the Court ordered that the jury be confined to a room, “to keep them without meat, drink, &c. until they agreed”.This had the desired effect, and they returned immediately with a unanimous guilty verdict.

In passing sentence, the Chairman noted that “Servants, […] who were put in trust, must not be allowed to plunder their masters without receiving a very severe punishment”. The ringleader Mansell was sentenced to fourteen years’ transportation to New South Wales – seven years for each of the two offences. The Court felt “sorry” for the other three, so they were given the lesser penalty of seven years’ transportation for the first offence, plus an additional week for the second theft.

William Rial, farm labourer, had become Convict 35/1184, and was never to see his wife Sarah or his infant sons again.

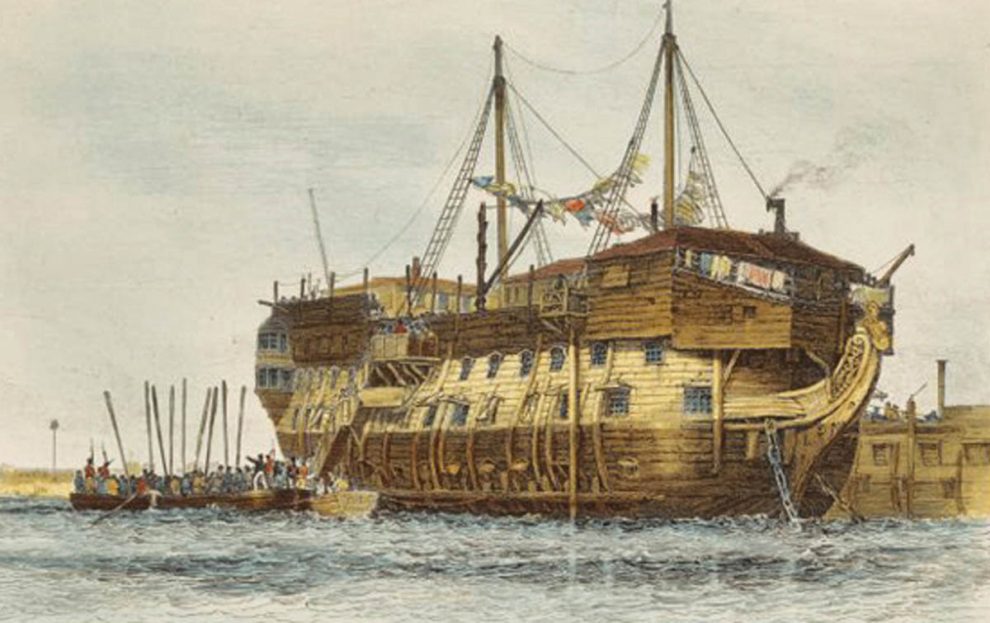

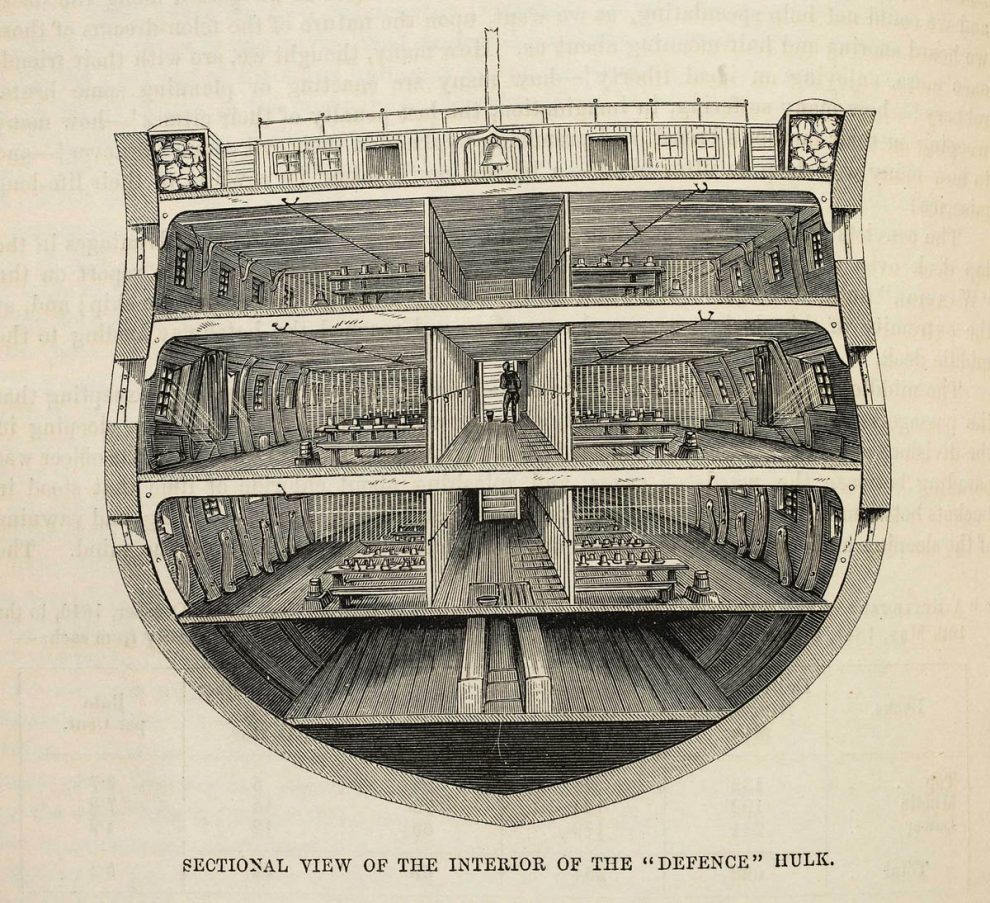

On the prison hulk HMS Fortitude

By the mid 18th Century, British prisons were overflowing. Transportation of convicts to North America had ceased with the American Revolutionary War, and the construction of new prisons was considered to be too expensive. So the Parliament authorised the use of decommissioned ships to incarcerate convicts as a two-year, stop-gap measure to deal with the crisis. This was the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). But the ‘temporary measure’ was repeatedly extended, ultimately for another 80 years, justified as being “for the more severe and effectual punishment of atrocious and daring offenders”. Around 60 hulks were employed over that time. They lined the Thames at Woolwich, and later spread to other locations including Chatham, Deptford, Portsmouth, Gosport, Plymouth, Sheerness, and Cork. Hulks were even commissioned overseas in Bermuda and Gibraltar.

One such prison hulk was the HMS Fortitude. It had been built as a ‘Repulse-class’, third rate (i.e. 74 gun) ship of the Royal Navy. Launched in 1807, it sailed as the HMS Cumberland, and achieved minor fame during the Napoleonic Wars when it was used to transport King William I back to the Netherlands. After becoming unseaworthy it was moored at Chatham on the River Medway (Kent). There it was stripped of its masts and rudder, and converted into a prison hulk in 1830. (It was renamed the HMS Fortitude in 1833.) As a hulk it could house between 200 and 300 prisoners at a time, while awaiting transportation to the penal settlements of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

Conditions on the hulks were appalling. They were overcrowded and unhygienic, plagued with vermin, and outbreaks of cholera, tuberculosis, typhus and dysentery were common. Many died in custody before they could be transported. In fact, during the first 20 years of the hulks, official records show that 2000 out of the 6000 convicts perished. A very small number are listed as having escaped.

Official records show that William Rial was “Received from Worcester” on the Fortitude hulk on 17 April 1834 – just 10 days after his conviction. Two of his fellow drinking companions (Richard Mansell and John Pitcher) arrived at the same time. William Beavan arrived three months later.

By day he would have done hard labour with other convicts, building the docks and dredging the river, before spending the night chained up inside the hulk. A separate section of the ‘Register of Prisoners’ contains notes about the behaviour and disciplinary actions taken against a small proportion of the convicts. These notes are sometimes quite illuminating, but for William Rial, there is just a cryptic and tantalising annotation: “Character bad”.

He spent a little over seven months on the hulk, before being “disposed of” on 26 November, along with John Pitcher and 98 other convicts from the Fortitude hulk, for transportation to the penal settlement at New South Wales.

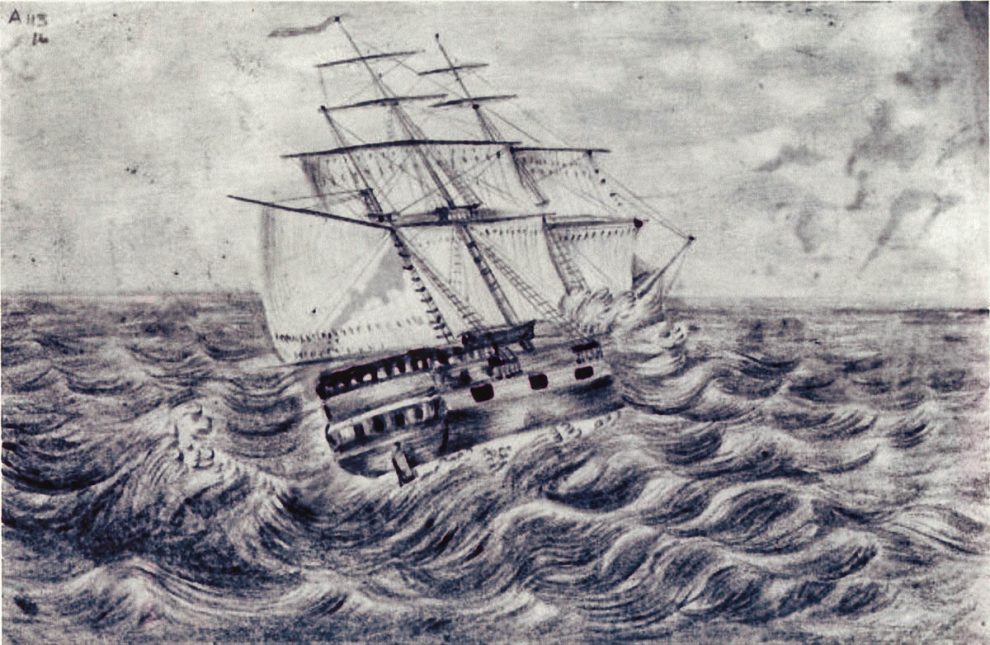

To New South Wales on the Lady Nugent

The Lady Nugent sailed from Sheerness in the Thames estuary on 4 December 1834, eight days after William came aboard. At the helm was Master Joseph Henry Fawcett, and Oliver Sproule was the Surgeon Superintendent, responsible for the well-being of the convicts throughout the journey.

The Lady Nugent was a three-masted, 535 ton ship built in Bombay as a private trader. She was launched in 1814, and for almost 20 years sailed under contract to the East India Company. She made two voyages transporting convicts to New South Wales (in 1834-5 and in 1836), and subsequently made four journeys to carry English immigrants to New Zealand. On her final journey in 1854 the Lady Nugent set sail from Madras for Rangoon, with over 400 Indian soldiers, passengers and crew on board. Overloaded and in poor repair, the ship sank in a storm, with the loss of all lives.

But at the time of William’s journey in 1834-5, the vessel was still ‘ship-shape’. It hosted a small number of free passengers, including eight women and 14 children – and 286 male convicts. Along with the 100 convicts received from the Fortitude hulk, there were 100 from the Justitia hulk, 60 from the Ganymede hulk (both located at Woolwich), and 26 convict boys (10 of whom were under 14 years of age) from the Euraylus hulk at Chatham. They were guarded by Captain Montgomery, Ensign Ruxton, and a detachment of 29 soldiers, all members of the 50th Regiment.

Their journey to Port Jackson (Sydney) took 126 days, which was about average at the time. Surgeon Sproule’s noted in his journal that the weather was cold and wet for the first week or two of the journey (it was mid-winter), and prisoners’ bedding in the leaky front end of the ship became saturated. Many fell sick.

After the Bay of Biscay the weather improved, which

“soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men”.

Nonetheless Surgeon Sproule was kept busy treating cases of catarrhal infections, dropsy, psora, boils, scalds and contusions – and thirty cases of scurvy. Two prisoners died en route. It wasn’t all grim:

“as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon”.

At Wanniassa with Thomas Macquoid

The Lady Nugent arrived at Sydney Cove on 9 April 1835, just 47 years after the establishment of the penal colony. Its arrival was announced with little fanfare in the ‘Shipping Intelligence” section of The Australian newspaper. But, as with all arriving vessels, the Lady Nugent brought keenly awaited ‘news from home’ in the form of four-month-old newspapers, large extracts from which were reproduced in the local papers. “The Duke of Gloucester has died!”, “Baron Paganini gave a concert in Parma, for the benefit of the poor”, “Hurricane in Domenica”.

It was one year and two days since William Rial had stood accused of cider theft in the dock at Worcestershire Quarter Sessions, and he now found himself at Sydney Cove. It was a place both very distant and very different to his former home.

The prisoners weren’t brought ashore immediately. They remained for 18 days on board the Lady Nugent, looking out across Port Jackson at their new and unwanted homeland, and it’s hard to imagine what hopes and forebodings they might have held about their future prospects.

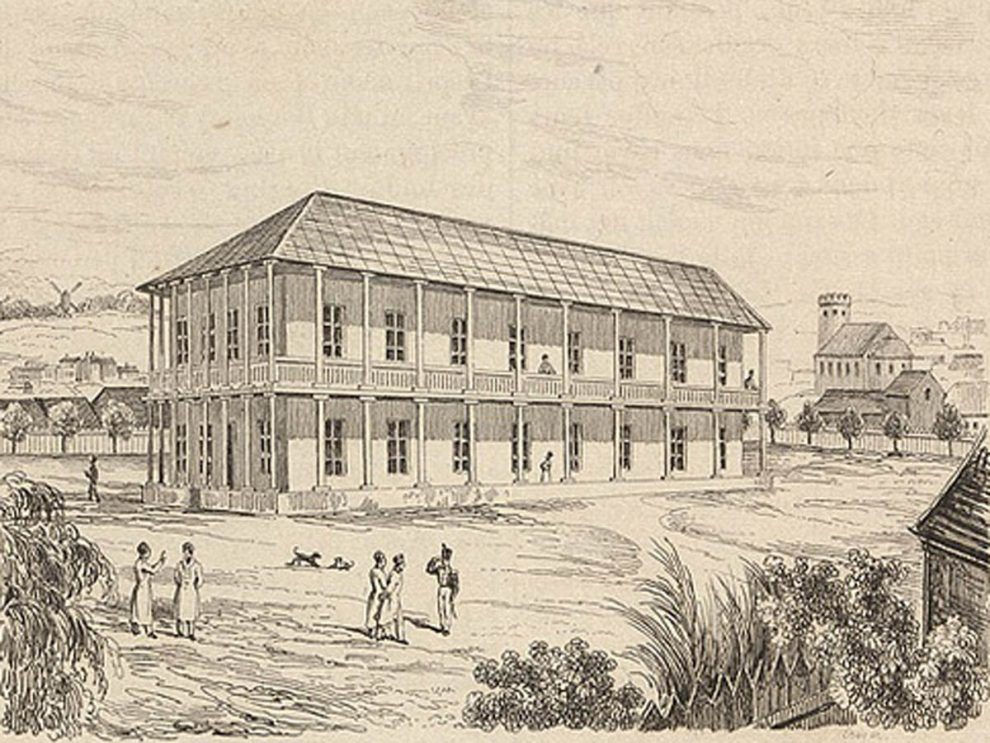

Eventually, on the morning of 27th of April they landed and were marched up the hill to Hyde Park Barracks to be mustered and assigned. The Barracks were built in 1819, under the governorship of Lachlan Macquarie, and were erected using convict labour. They were intended to house 600 convicts, but at times there up to 1400 men there, sleeping in rows of hammocks. Few convicts stayed long in the Barracks. Long-term residents were mostly those who possessed particular trade skills, making it desirable to retain them for government service in Sydney. But the majority were quickly ‘assigned’ to work under close supervision on properties and in businesses around the fledgling, but rapidly expanding, colony.

Of the 284 convicts who arrived on the Lady Nugent, 151 were ‘Assigned to Private Service’. Another 75 were ‘Reserved by Government”, 44 were sent to quarry stone on Goat Island, nine went straight to hospital, and five were recorded as “Specials”.

Thomas Macquoid

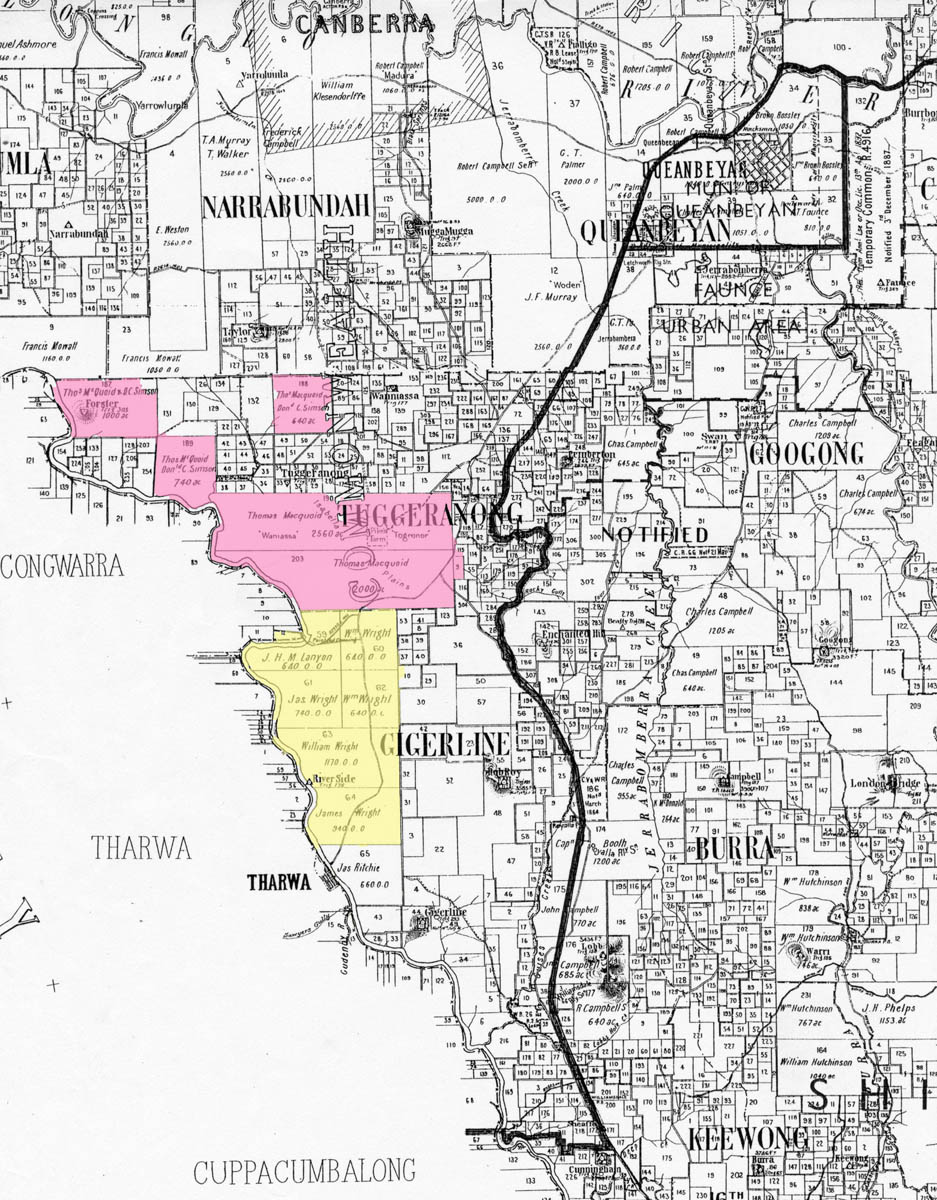

William found himself assigned to work for Thomas Macquoid, who was Sheriff of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. He made the journey down to Ngunnawal land on the Limestone Plains (now Canberra) to work on Macquoid’s property as a farm labourer.

Macquoid’s own life story is a classic and fascinating tale of colonial life – full of exotic adventure, and ultimate tragedy. He was born in 1779 in Ireland, and after time in Canton and Macau, he served as Sheriff of the Court of Judicature in Penang in 1808-9.

He became a close friend of the famous Sir Stamford Raffles (Lieutenant-Governor of the Dutch East Indies, and founder of Singapore), who appointed him as Malay translator to the colonial administration. He spent time in Ambon in the Spice Islands (Maluku), and moved to Bogor (Java) in 1812 where Raffles made him Superintendant of coffee cultivation, and Chair of the Commission of Land Sales in West Java. In 1817 he returned briefly to England, where he married Elizabeth Kirwan, then returned with his bride to Batavia.

As was common amongst his contemporaries, he sought to acquire a quick fortune, through a combination of laissez-faire capitalism, exploitation of his powerful position, the local population and resources, and sometimes questionable business practices. He got involved in speculative business activities which at first flourished, but then collapsed in 1825. Raffles himself lost £16,000, a huge sum at that time, which he had invested in Macquoid’s firm.

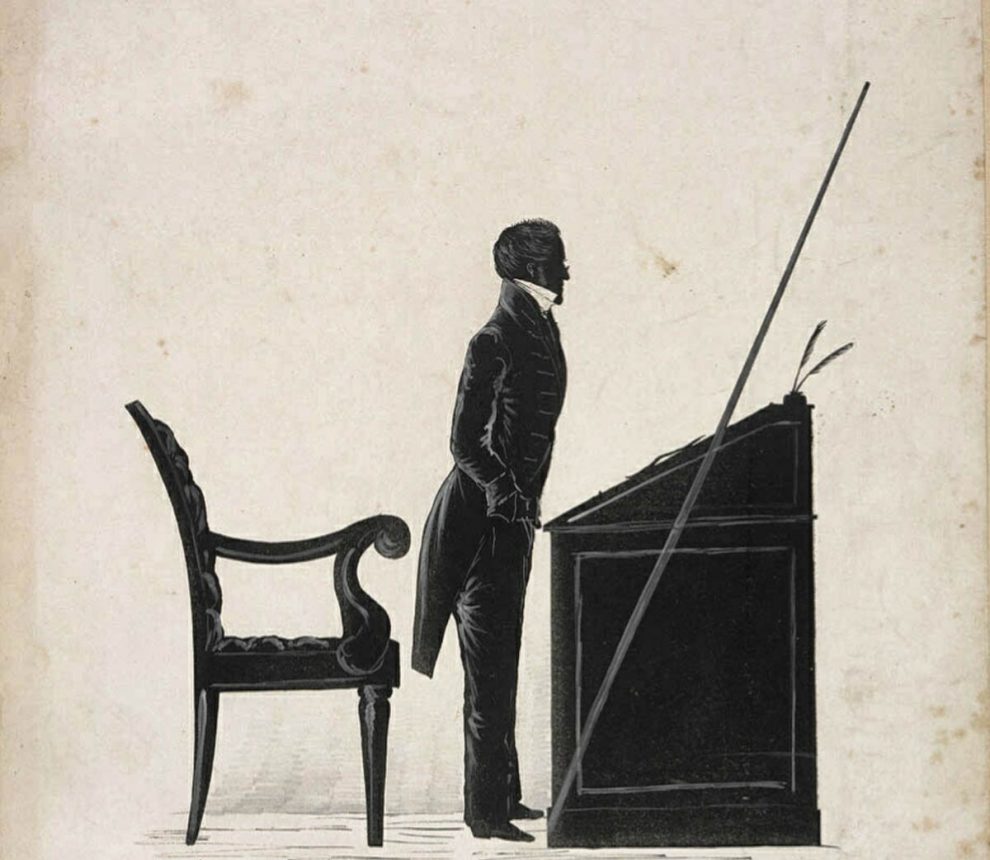

[Album of portraits, mainly of New South Wales officials, ca. 1836] / by W.H. Fernyhough No.4 Sketches from the Bar Sheriff Macquoid Silhouette by W.H. Fernyhough (1809-1849) https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/digital/file/ZyGEdG5NLEAo2

Back in England and financially embarrassed, Macquoid’s fortunes improved when, through the influence of the Secretary of War, Viscount Goderich, he was appointed to the post of Sheriff in the Supreme Court of New South Wales. He arrived in Sydney in January 1829, and had a large mansion built in Darlinghurst – which he named Goderich Lodge in honour of his benefactor.

As Sheriff, Macquoid was a busy man, being responsible for ensuring the execution of all judgments of the Supreme Court (including death sentences), transport of prisoners, running the gaols, and serving as both Coroner and Marshall of the Admiralty.

From 1830, as a sideline to his prestigious position in Sydney, Macquoid ran sheep on land in the Tuggeranong valley near Queanbeyan, which he formally purchased in 1835. The area had only been opened up for colonial settlement since 1829, and a rush of land claims and purchases soon followed. The Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, who had lived in this area for at least 20,000 years, were pushed aside.

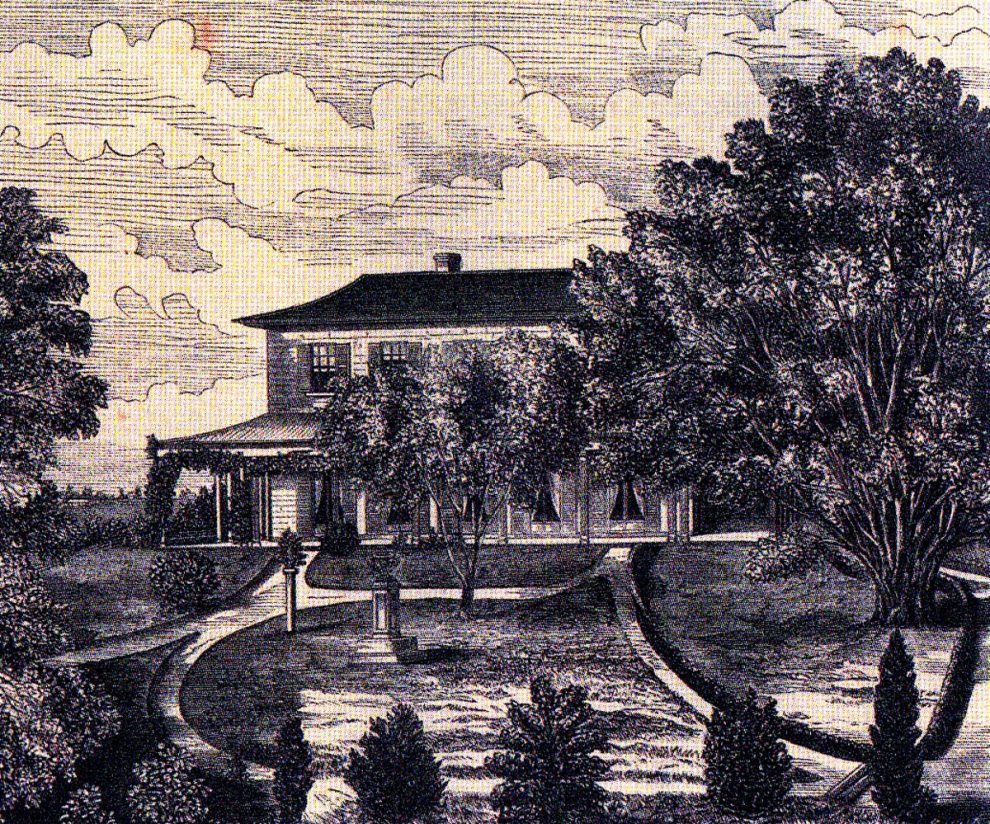

Macquoid named his own property ‘Wanniassa’, after his residence in Java (at ‘Wanayasa’). He had a stone cottage and barn (parts of which still exist at the ‘Tuggeranong Homestead’) built with convict labour, and expanded the property north into the Tuggeranong valley.

But, echoing his experience in Java, Macquoid suffered a series of legal and financial setbacks. He had failed in his attempts to have the office Sheriff given the official status and remuneration that he believed it deserved. His rural pursuits were badly hit by a severe drought (which had begun in 1838), by plummeting wool prices, and by the ensuing economic difficulties of the colony. Fearing that another bankruptcy was imminent, he became severely depressed.

In his dressing room at Goderich Lodge, at about 6:00am on the 12th of October 1841, he wrote an emotional and somewhat incoherent note to his wife Elizabeth, who was sleeping in the adjacent bedroom. Then, with one of the loaded pistols which he kept in his dressing table, “the unfortunate gentleman put a period to his existence”.

It turned out that his financial situation was not as dire as he had believed, and his eldest son Thomas Hyacinth Macquoid (‘Hya’) was able to stall off creditors, pay off the debts, and manage the property at Wanniassa profitably for many years. But Hya Macquoid’s own life was to end in tragedy when, returning from a visit to England, he was drowned in the wreck of the Dunbar off the South Head of Sydney Harbour in 1857.

Date prior to 1841

But by then, William Rial was long gone from Wanniassa. Five years after his conviction, on the 29th of May 1839, he received his Ticket of Leave, under the terms of which he was obliged to remain within the district of Queanbeyan. He was now free to seek private employment, and even to bring his family to the colony from Worcestershire if he so chose. However this may have been prohibitively expensive, and there’s no evidence that he sought to reunite with his wife Sarah and two sons, who were by then eight and five years old.

At Lanyon with James Wright

By 1841, according to the records of the Ticket of Leave Muster, William was employed by James Wright as a farm labourer at Lanyon, less than 10km south of his former assignment with Sheriff Macquoid at Wanniassa.

Later in that year Rial gained his Certificate of Freedom (on 28 July 1841). His seven-year term of punishment had been served, and he was a now free man – but he was alone, and far from his family and former life in Worcestershire.

At some time prior to 1834, John Lanyon and James Wright (born 1796, arrived in New South Wales 1833), originally from Derbyshire, established a pastoral property of around 5000 acres on the banks of the Murrumbidgee River. Lanyon returned to England in 1836. In the same year James Wright’s brother William arrived to help manage the property, but didn’t manage to provide much help; on New Year’s Day of the following year he was killed in a duck shooting accident.

While William Rial was still working as a Ticket-of-Leave holder at Lanyon in 1841, the New South Wales Census was conducted on the 2nd of March. At that time William was just one of the 59 people living at the Lanyon property, 49 of whom were males. Six were Ticket-of-Leave men, and 25 were assigned convicts. At that time Lanyon boasted 4000 sheep, 400 cattle, 24 bullocks – and six pigs.

The census also records another 19 men and one woman at Wright’s other property at ‘Port Hole’ (later to be renamed ‘Booroomba’). 16 of these were identified as “Shepherds and others in the care of sheep”. 13 were classed as convicts “In private assignment”, two were Ticket-of-Leave holders, and just five were “Free persons”.

The property at Lanyon seemed to be flourishing but, in the familiar pattern of the boom-and-bust economy of the 19th century, James Wright accumulated large debts. By November 1843 he had become insolvent, and a large number of creditors, including 22 ‘servants’, petitioned the NSW Supreme Court for wages and other debts owing to them. In a sworn submission to the Court, William Rial asserted that he was owed £15 11/- 7d.

After the sale of household effects and other assets, his creditors were paid off, but James Wright was eventually forced to sell Lanyon in 1849. He relocated to a new property across the river and to the south of Lanyon called Cuppacumbalong.

William Rial was still working at Lanyon in 1843 as a free man, although forever tainted by his convict background. It may be that, in order to distance himself from this past, from this time on he always spelt his name as ‘Rial’ – rather than ‘Royal’, which was how it appeared in all of the records from his convict years.

Then, by 1846 at the latest, he had moved on to new employment – and to start a new family. We’ll put William Rial’s story on hold briefly, to introduce the family of his new in-laws.

At Milford with William Williams

William Rial’s future father-in-law William Williams arrived in Sydney as a free settler on 27 August 1827. He was a “Barrister at Law, son of Mr Williams, a Professional Gentleman, of high reputation in London.”

A fatal duel

William Williams’ journey on board The Harvey was, to say the least, not without incident. He and another passenger (J. Noble, a merchant and a relative of D’Arcy Wentworth) got into “some disagreeable misunderstandings” with three lieutenants of the 55th Regiment who were also on board. Tensions between the two passengers and the soldiers escalated throughout the journey from England to Cape Town. In Capet Town, and in response to continued verbal abuse from Williams, each of the lieutenants formally challenged him to duel with pistols. Williams readily accepted, and with weapons loaded, “strange to say, he fought three in succession – wounding one, very nearly quieting the second, and not returning the fire of the third, who quitted the field”.

But the lieutenants had not finished seeking satisfaction, and they also challenged Williams’ friend Noble to duel. Noble slightly wounded the first one, and then shot the second lieutenant in the head, killing him instantly. Williams and Noble were arrested and tried for murder under Dutch law in Cape Town, but acquitted “for want of sufficient evidence of the duel having taken place”! A Military Court of Enquiry was also convened, which found that the lieutenants’ commanding officer (one Captain Elrington) was culpable for not adequately controlling his subordinate officers’ behaviour. Elrington was arrested and sent back to England; Williams and Noble were released and re-embarked on The Harvey to continue their journey to Sydney via Hobart without further incident.

William Williams in Sydney

William Williams was a solicitor, and clearly a man of action. Within five days of his arrival in Sydney he was admitted to practice in NSW by the Supreme Court. The 1828 Census records him as living in Pitt Street, Sydney, and as being the owner of a horse and two cattle. He had three assigned convicts at this address – one (Joseph James) working as his clerk, and another married couple (Elizabeth and Michael Ryan) listed as ‘servants’.

Mentions of his court appearances frequently appeared in the Sydney Gazette, mostly in connection with insolvency cases.

But another court report from 1828 recounts Williams’ servant Michael Ryan testifying that he disturbed a burglar in the act of ransacking his master’s home office. He intercepted the thief as he jumped out of the office window onto Pitt Street, whereupon he

“struggled with the fellow lustily but was several minutes before he could obtain assistance, and it was not improbable that the eloper might have given witness the cut and run had not a constable stepped up, by whose assistance the prisoner was finally secured and transported into the receiving arms of the highest watch-house”.

The prisoner (Phillip Reilley) offered no defence against the charges. The jury retired, returning almost immediately to deliver a ‘Guilty’ verdict. Reilley was back in court a week later for sentencing, as briefly noted in The Australian newspaper:

“Phillip Reilley, indicted for, and found guilty of, entering the dwelling house of Mr William Williams, in Pitt-street, Sydney, and stealing therefrom property above the value of £5 – judgment of death recorded.”

(I couldn’t find a record of Reilley’s execution, so I don’t know if the sentence was ever carried out.)

On 24 September 1829 William Williams became the father of Adelaide Louisa Williams- later to become William Rial’s second wife (and my great-grandmother).

Margaret Campbell/Robertson/Williams

Adelaide’s mother was 26-year-old Margaret Robertson (nee Campbell). Margaret had migrated to Hobart from Lochend in Scotland on the ship Lusitania, along with her parents and eight of her 12 siblings. The journey took 140 days, and they arrived in Hobart on 29 October 1821. Her father John was well-connected, a Colonel in the British Army, and travelled with a letter of introduction to Governor Macquarie from the Secretary of State for the Colonies.

In Hobart on 14 February 1822 Margaret married James Robertson, who had arrived on the same ship (the ‘Lusitania’)as the Campbell family.

James acquired land at ‘Emu Bottom’, and in 1822 joined the committee of the Van Diemen’s Land Agricultural Society. In 1824 he advertised the sale of “One Hundred EWES and LAMBS from the highly improved and well known Flocks of James Robertson Esq”, at his property Catrine Vale on the Clyde River.

On 4 February 1825, that same journal reported that

“A flatterer in rhyme, whose name is Hugh Campbell, and who calls himself an ” humble-proud Bardie,” has published some nonsensical verses addressed to Mr. James Robertson, of Emu Bottom, whom he describes as a ‘Gentle Shepherd, WHO HAS BROUGHT MORE VIRTUES TO VAN DIEMEN’S LAND, THAN WILL COUNTERACT THE VICES OF TWELVE CARGOES OF OTHER SETTLERS !!!’”

Margaret and James had three children (a son and two daughters), but the marriage was short-lived, and they appear to have separated in 1826.

Margaret and the children moved from Hobart to Sydney on board the ship Albion on 8 June 1826. In 1830 the children, accompanied by their father James Robertson, returned to Scotland. From that time the children were cared for by James’ mother’s family, the Buchanans. James himself died unexpectedly in 1834.

The eldest of James and Margaret’s children (James Jnr) subsequently returned to live in NSW. He worked as a drover for a time, but died young (in 1850).

Of the daughters, Annabella married James Campbell, a British soldier of the 7th Madras Cavalry, and lived for many years in India. The last born was Margaret Buchanan Robertson, who would only have been three or four years old when separated from her mother at the dock in Sydney Cove. She remained single throughout her life, living in genteel poverty and indifferent health back in Scotland. Neither of the daughters ever saw their mother again, but continued to correspond regularly with her throughout their lives. The letters that have survived are often quite poignant:

- Margaret Buchanan writing in 1844 (when she would have been 17 years old):

“perhaps you may have the pleasure of being once again surrounded by your children who I trust are worthy of their mother’s love… My height is five feet five which I think is a very good height for a young lady. I am still very fair with rosy cheeks light eyes and fair hair… in this letter I send you a piece of my hair and some violets which I hope will retain their scent till they reach you ” - Annabella in 1855:

“Oh my own dearest Mama I think I see you now as I last saw you leaving us on board the ship telling poor wee Maggie that you were going to buy her a softer bed – How often your figure rises up before me. How cruel it is to take a child from its mother. Even at this moment that long yearning to be folded to your bosom is on, & I feel ready to throw myself down and cry that it cannot be. God grant us a meeting in Eternity.” - Annabella in 1856:

“..my beloved Mother never think your two girls do not think of you with warm warm love… God bless you my dearest Mama & grant I may hear from you soon”

But let’s return to Sydney in 1827. On 19 January Margaret’s estranged husband James had assigned to Margaret all of his sheep, other livestock and goods and chattels. On 27 July Margaret Robertson advertised in The Australian of her intention to open a school in Parramatta “to Board and Instruct young Ladies in the different Branches of polite Education”.

The Census of 1828 places her at 31 Pitt Street Sydney (could that have been William Williams’ residence?), and the owner of 20 cattle and 500 sheep – undoubtedly those which had been assigned to her by James, and which presumably resided elsewhere. She was described in the Census as a ‘schoolmistress’ and a Protestant.

Following the birth of Adelaide in 1829, she and William Williams had a second child (William Henry), born on 2 April 1831. On 5 February 1835 they received word from Scotland, advising of the death of Margaret’s husband James. Williams immediately wrote to Governor requesting approval to marry Margaret. He must have received an instant reply, because Margaret and William were married later on that same day, by special licence. On the marriage record she was described as a ‘widow’.

Milford

By the time of their marriage, William Williams had (temporarily) abandoned his career as a solicitor. He was struck off the Supreme Court roll in 1830 for failing to practice law during the preceding year, and had acquired a property which he named Milford, on the Yass River near Gundaroo. This area west of Lake George had only been ‘discovered’ by Europeans in 1820.

Margaret already had a family connection to the Gundaroo region. One of the first Europeans to ‘take up’ land at Gundaroo was a Dr Donald McLeod, who had previously served as Superintendant of Agriculture at both Bathurst and on Norfolk Island. Donald’s brother Archibald McLeod was married to Margaret’s sister Colina, and two of Margaret’s nephews worked on the Gundaroo property named Bernisdale (after the McLeod family home in Scotland). Archibald was later to establish the station at Bairnsdale in Victoria, the site of the modern town of the same name.

Between 1834 and 1838 William Williams variously advertised in the Sydney papers for a station manager, a bullock driver and an overseer for his farm Milford. In the 1841 census, seven people were recorded as living at Milford. In addition to the Williams family (William, Margaret and their children Adelaide and William Henry), there were three single males, two of whom were ticket-of-leave men. Their occupations were listed as mechanic, shepherd, and domestic servant.

It’s unclear how much time William Williams actually spent at his Milford property. All was not well with his and Margaret’s marriage, and they seem to have spent much time apart. Margaret’s brother-in-law Archibald McLeod wrote to her (18 Jul 1839), offering advice: “You ought not to make any attempt to relieve Williams for the present. You may think this bad Counsel but I can assure you it is well meant, had he years ago the lesson he is now getting it might have made a cure, and it is my belief that his Complaint is as difficult to get rid of as a bad corn.” The nature of Williams’ ‘complaint’ is not made clear.

In January 1842 he was re-admitted to practice as a solicitor, with chambers at 5 Bridge Street in Sydney. He also seems to have practised law in Goulburn, in partnership with his brother Horatio Wright Williams. But business can’t have been good, for on 22 September 1843, the NSW Government Gazette reported the sequestration of his insolvent estate.

William Williams’ brother Horatio had come to New South Wales in 1837, leaving behind a wife (Anna Maria Williams) and a baby daughter in England. It seems that Horatio was something of a wastrel, and may have left England in disgrace.

Anna Maria wrote him a very frank letter as he sailed to Sydney. She admonished him to

“alter that dreadful course of life you have been pursuing, forsake that desperate diet of drinking, be industrious for a few short years and then with what unalterable joy should I clasp thee to my bosom… how you have disappointed me! … I have a faint hope that now we are separated so many many thousand miles you may sometimes be induced to think of the grief that you have occasioned to a heart that still loves you, and that it is yet in your power to heal the wound…. forgive me if I say reform, if not alas! I fear we can never meet again in this world…

Take care of yourself for remember you are not in a civilised country like England.”

The partnership with his brother Horatio was not long-lasting, as William Williams died a few years after it was established – probably in 1845.

Wilful murder

His widow Margaret appears to have remained at Milford until about 1854, where she experienced dramas of her own. In 1843 she took up further leases nearby on the Yass River in her own name. Then one day in March 1845, Margaret sent a servant out to purchase some wine. On his return with the wine he encountered William Berry, another Milford employee who worked there as a ‘sheep watchman’. Berry persuaded him to hand over the wine, and to tell Margaret that he had been ‘bushranged’ and the wine stolen. Margaret believed this story until her son (William Henry, then aged 13) told her that he had seen a drunk woman at Berry’s hut.

She sent her overseer, a man named James Astell, to visit the hut, where he found the wine in the possession of Berry, who was by then thoroughly intoxicated. Berry followed Astell back to the farmhouse in a drunken rage, where he proceeded to abuse Margaret and Astell “in foul language”, and threw a footstool at the poor overseer. Astell ordered Berry to leave, and threatened him with a tomahawk. In turn Berry threatened Astell with a piece of fence timber, and Astell hit him on the back with the tomahawk, and sent young William Henry off to fetch some “percussion caps”, which were stored three miles away.

When William Henry returned, Berry was still “behaving outrageously”, causing Astell to retreat into a storeroom where he barricaded himself in. Berry tried to break into the storeroom to attack Astell with a knife, and Astell threatened to shoot him if he didn’t leave the farmhouse. Berry replied: “you know better, and you’re not game!” Those were perhaps his last words, for Astell did indeed shoot him (in the side), and he died some seven hours later.

The Magistrate in Yass committed Astell on charges of both wilful murder and manslaughter. The jury heard evidence from Margaret, her children William Henry and Adelaide Williams, as well as Sergeant Herbert of the Goulburn Division of Mounted Police. Astell was found guilty of manslaughter, for which the judge, taking “a very merciful view of the case”, sentenced him to 18 months in Parramatta Gaol.

Just weeks later (13 April 1845), it was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald that the same Sergeant Herbert who responded to Berry’s killing had “apprehended … three armed bushrangers, who recently robbed the station of Mr Williams on the Yass River”. Wild times on the Yass River.

William Rial at Milford

It must have been around this time that William Rial arrived at Milford, Gundaroo. One possibility is that he was employed to replace the jailed overseer James Astell. Whatever the circumstances, he had by mid-1846 established a relationship with the young Adelaide Louisa Williams. At that time he would have been 39 years old, and she was just 16.

The first of their ten children, William Henry Rial, was born at Gundaroo on 11 April 1847. A second child, Ellen, followed on 29 June 1848. William and Adelaide were married at Gunning on 7 May 1849, and it was only after this that their two children were baptised.

On the registration of the wedding, William was described as a ‘Labourer’ and a ‘Widower’ – even though his first wife Sarah was still very much alive back in Worcestershire. Census records from 1851 show that Sarah Ryall (by then aged 41) was living with her 19-year-old son John at the Hartlebury Rectory. She was a nurse, and he a footman. Sarah and William’s second son (‘William Royal’) was at that time 17 years old, and working as a carpenter/journeyman in Worcester.

While still living at Gundaroo, William and his new wife Adelaide had two more children – Susan (born 15 Jun 1850) and James Edward (born 17 Sep 1851). But the two daughters (Ellen and Susan) passed away in infancy, dying within a week of each other in April 1852.

By the time of Susan’s and James Edward’s baptisms, William had progressed from being a ‘Labourer’ to a ‘Farmer’, and sometime around then he entered into a partnership with Adelaide’s brother William Henry Williams.

At Four Mile Creek

By 1854, William and Adelaide had left Milford and moved south, settling on land at Four Mile Creek (Little Billabong, to the north of Holbrook). Adelaide’s mother Margaret seems to have moved with them. Ownership of the land was achieved in 1856, when title was transferred from J.C. Whitty (who had held the land since 1850). Rials were to occupy Four Mile Creek for another 52 years. William Henry Williams bought land nearby, at Carabost.

Between 1854 and 1865, William and Adelaide had another six children (two daughters and four sons) at Four Mile Creek. Amongst them, born on 16 September 1860, was my grandfather Archibald Joseph (‘A.J.’) Rial – presumably named in honour of Adelaide’s uncle Archibald McLeod . With the business name ‘Rial Bros’ the sons went on, through boom and bust, to establish something of a pastoral empire, owning a number of properties across the Riverina and Western Plains of NSW.

From a letter published under his name in the Border Post, we know that in 1861 William Rial operated an Inn at Four Mile Creek called the ‘Traveller’s Home’, and conducted picnic races there. In this long letter to the paper, he responds with righteous indignation to an earlier item written by a ‘Mr King’, which had suggested race-fixing or some other improper goings-on. In outraged tones he wrote:

“If there is any one thing more indispensably necessary than another in an article intended to meet the public eye, it is accuracy, or to speak more plainly, truth.”

These sound like the words of a morally upright colonial grazier. But William himself had sought to obscure the truth, and to ensure that some facts of his own life did not ‘meet the public eye’ – including his convict past, and the inconvenient fact of his wife and family back in Worcestershire. There’s nothing in the family’s oral history or available correspondence to show that the next generation was aware of his true story. His children either did not know, or else considered the history too shameful to discuss. We can only speculate about what Adelaide knew of her husband’s past.

William Rial died in the Imperial Hotel, Albury, on the 9th April 1867 – which coincidentally was the 32nd anniversary of his arrival in New South Wales. In his 60 years he had lived several eventful lives, often swept along by chance, and forces beyond his control. He began as a farm labourer, became a convicted felon, and ended as a successful grazier and founder of a large pastoral enterprise. He left behind two wives and 12 children, who were later to produce 60 grandchildren.

The cause of death was listed as bronchitis, at the end of an illness which had lasted six days.

His wife Adelaide Louisa Rial of Four Mile Creek was listed as the ‘informant’. She married again, in 1870, to John Wanklyn, and bore another two children with him. Adelaide herself died in 1894, aged 64, and was buried in the Albury Cemetery, alongside William.