The Bushranger is an iconic figure in the mythology of colonial Australia. They still appeal to our sense of national self-identity because we see them as being brave, independent, charismatic, anti-authoritarian, and resourceful. Underdogs, tragic heroes. Just like we’d like to imagine ourselves to be. The reality is that most lived pretty sordid and short lives, and were often quite unpleasant and disloyal in their personal affairs – more ‘squalid hood’ than ‘Robin Hood’.

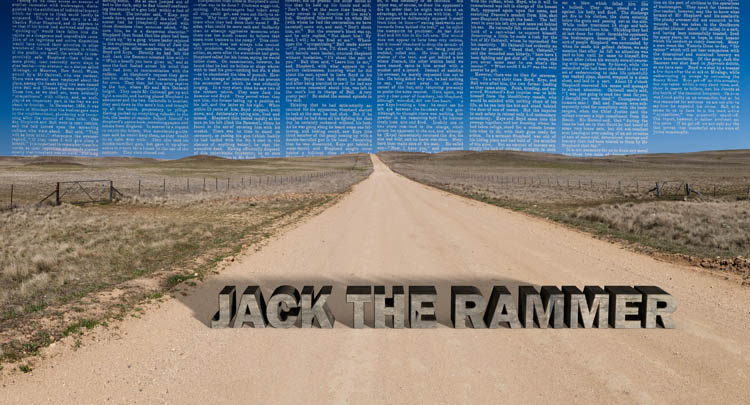

Bushrangers were active in the Monaro region during two periods of the 19th Century. Firstly during the late 1820s and ’30s, when most were escaped convicts, and then again around the early 1860s while the gold rushes were in full swing at places such as Kiandra and Araluen. For a few months at the end of 1834 “Jack the Rammer”, along with fellow gang members Edward Boyd and Joseph Keys, ranged across the Monaro. Jack the Rammer, a.k.a. “Billy the Rammer”, is believed to have been William Roberts, who was transported in 1833 from Dudley his native Worcestershire after being convicted for stealing a bucket.

(A personal coincidence here: my great-grandfather William Rial was born a short way from Dudley in the village of Hallow, and was himself transported in 1835, and assigned to work at Wanniassa station, just to the north of the Monaro).

After escaping with Joseph Keys from Goulburn Jail in September 1834, Roberts and Keys joined up with Boyd, and the three began a series of nocturnal robberies on stations of the Monaro, including Coolringdon, 10km southwest of Cooma. In the course of holding up Rock Flat station in mid December, The Rammer was shot and killed by the station overseer Charles Fisher, who was himself shot, beaten and left for dead by the other two outlaws. Boyd was shot dead by a trooper in mid-January while trying to escape across the Snowy River, and Keys was captured two days later at Jimenbuen, tried and hung in June 1835. Like many bushrangers, the gang had a short, bloody and spectacularly unsuccessful career.

The base photograph for this image was taken on the Springfield Road, not far from Coopers Lake, not too far south of where ‘The Rammer’ met his end. The newspaper text (from the Christchurch Star, 8 April 1879) is a lurid account of the exploits and demise of the Rammer Gang.