After we left the Tiwah at Kuala Kurun, we continued northwest, up to the last villages near the headwaters of the Kahayan River.

The population is largely Dayak – Ngaju and Ot Danum – and mostly quite religious, with Christian churches and Kaharingan animist structures (sapundu, pantar, and sandung) side-by-side, and seemingly around every corner.

As is usually the case in Kalimantan, the journey was as much of an adventure as the destination. This part of Gunung Mas regency is really interesting, rich in culture, history – and full of challenges for the traveller. We had the good fortune to be accompanied by our guides and friends Dodi and Jonathan, both Dayak, who have deep knowledge of the area.

The road up to the Upper Kahayan (Kahayan Hulu) sub-district is asphalt in parts, but is mostly dirt, sand or more often (at this time of year) mud. We encountered the road closure above while running repairs were being made to a small bridge. Chainsaw, hammer, and some six-inch nails soon made it usable again, though other drivers got us to cross first in our sporty red Land Cruiser, before chancing it themselves.

Further down the ‘highway’ were a number of steep and/or muddy patches. The motorbike rider above had chains around his rear wheel to try and get some traction through the mud. That’s Dodi walking behind him in the white t-shirt. He’d gone back down the road to retrieve a mud flap that got torn off our Land Cruiser when we came through. By the end of the day we had hauled out a couple of vehicles which had become bogged in deep mud.

We arrived and Tumbang Anoi after dark, and settled in for our stay at the famous longhouse. The next morning, our 4WD got a much-needed wash and some running repairs.

The longhouse (betang) at Tumbang Anoi was built in the late 1800’s by Damang Batu. But unfortunately it is no longer habitable, and we stayed in the ‘new’ betang built adjacent to the site of the original one. It’s still an impressive structure, built entirely from kayu ulin (Borneo ironwood). It sports modern conveniences such as running water, but currently the pump is not working, so buckets of water were carried up those steep steps each day so I could wash at the mandi (and we could flush the toilet). Karen, more considerately, chose to bathe in the Anoi river behind the betang.

The sandung and sapundu in front of the betang are beautifully carved, and in a style unlike what we’ve seen elsewhere.

All that remains of the of Betang Damang Batu is some of the wooden framework. The site is overgrown with weeds now, and it looks a little forlorn, but for three months in 1894 it was the centre of the Dayak world, and events there helped shape the subsequent course of Borneo history.

Before that time, fighting between the many and various Dayak tribes of Borneo was chronic, and (perhaps due to the disrupting impact of the Dutch and British colonial powers) was getting worse. Headhunting raids led to revenge raids led to more raids, and the cycle was accelerating. One ongoing war between Dayak Ngaju of Central Kalimantan with Kenyah from the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan had led to many deaths on both sides – and no victor.

At a meeting convened by the Dutch Resident from East Kalimantan in Kuala Kapuas in June 1893 it was decided to hold a grand council of all the leaders of all the Dayak tribes of Borneo. 152 were invited. Damang Batu, the 73-year-old Ot Danum chief from Tumbang Anoi, was widely respected by all, and he offered to host the meeting in the following year.

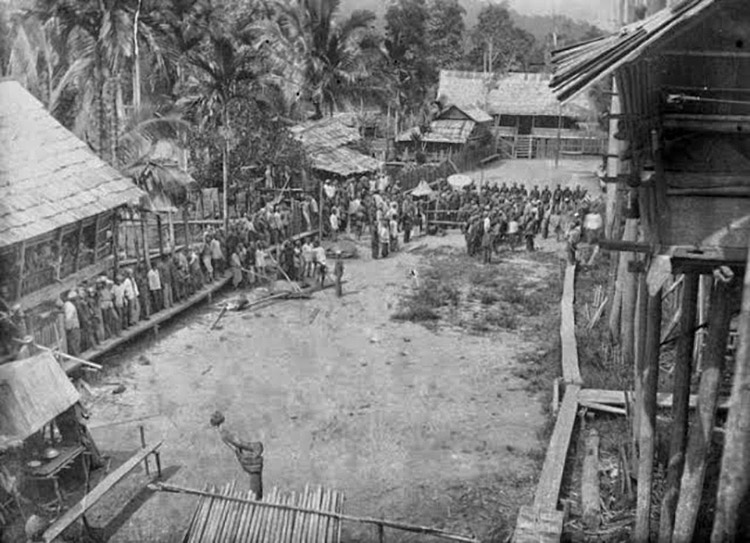

The meeting, a photo of which is above, was a great success. It lasted three months, and the catering reportedly included 100 buffalo, 100 cattle, and countless pigs and chickens. By the end, there was agreement to immediately:

- cease hostilities between the tribes, specifically the ‘3H’ practices of Hakayou (raiding parties), Hapanu (killing each other) and Hatekek (the taking of heads);

- cease the practice of human slavery; and

- enforce the rule of customary law, including payments in the event of someone killing a member of another tribe.

The council of Dayak chiefs also found time to consider and rule on some 300 previously unresolved disputes and criminal cases.

In front of the betang – and in front of just about every Dayak Kaharingan home is a plant known in this part of Kalimantan as Daun Sawang (or Dawen Sawang) [Cordyline fruticosa]. The leaves of this locally sacred plant are used in a number Kaharingan rituals, where they may be used to splash water (or blood of sacrificed animals). Hung from a line suspended between poles the leaves can indicate the perimeter of a ceremonial area.

Tumbang Anoi has an official population of 418 (in 116 families). But this is possibly exceeded by the population of carved sapundu figures that stand mutely throughout the village. Some looked as though they could start speaking at any moment.

Buei Tiung (the ‘Keymaster’ of the betang, standing in front of the group above) walked us around the village and tried to explain some of the history and culture. He introduced us to many of the locals along the way, including Buei Raden Sawang, the village elder at the left of the photo above.

The kids were unusually shy, perhaps because it is rare for them to see people like us in Tumbang Anoi. The cry goes out: “Ada bule di kampung! Bule di sini!” (“There are white-skinned people in our village!”) These kids just ran away at first, then got curious and approached us slowly from behind, running away again every time we turned to face them. Eventually they tentatively agreed to pose for a photograph, but even then they clung to each other for courage.

We went upriver by klotok longboat to the hospitable villages of Karetau Sarian and Tumbang Mahuroi, which are the last (or first, depending on how you look at it) villages on the Kahayan River. With peaks of the Schwaner Mountains in the background, this is real ‘Heart of Borneo’ country.

The traditional crafts are still practiced in places like this. The lady above is making a small basket, while a half-complete woven mat can be seen at the back of the room.

Some children’s games seem to be just about universal. These boys were expert marbles players.

A juvenile Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris) was being kept as a pet in Karetau Sarian village. These birds are the smallest and most widespread of the hornbills, and unlike some of their larger cousins, are not considered to be under threat. But this beautiful little bird looked like he would rather be free in the forest than a captive in the village.

The main industry of the upper Kahayan appears to be (illegal) gold mining. Floating dredges are used to sift alluvial gold from river sand (as is common practice in our own area along the Rungan River), but there are also mining sites dotted along the river banks. These operations pump high pressure water into the sand/soil mix of the river banks, forming a suspension of muddy gold-flecked water which is then filtered in the same way as used on the alluvial dredges.

With the steady disappearance of the forests, changing social values, and the collapse in rubber prices, the money that comes in from gold mining is keeping whole villages afloat economically. But… this activity also causes massive damage to the river banks, and causes the rivers to be even muddier and siltier than they would otherwise be. A particular problem results from the miners’ use of mercury to extract the gold flecks from the dirt and sand etc. A proportion of the mercury ends up in the rivers, whose fish all now have high levels of mercury contamination.

Captive hornbills, and toxic gold. As so often in Kalimantan, the sublime and the tragic sit side-by-side. Some further reading about Tumbang Anoi;

- http://humabetang.web.id/artikel-dayak/2013/perjanjian-dayak-tumbang-anoi-1894/1

- http://kulturdayak.blogspot.co.id/2015/07/dokumentasi-perdamaian-tumbang-anoi-1894.html

- http://gerdayakjakarta.blogspot.co.id/search?q=anoi