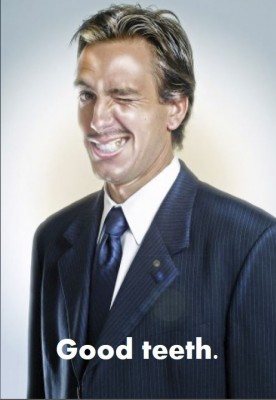

I met ‘The Land’ in a dream. He looked to be about 35, average height, with dark hair slicked back from a smooth broad forehead, pencil-thin moustache and sideburns. Good teeth.

I met ‘The Land’ in a dream. He looked to be about 35, average height, with dark hair slicked back from a smooth broad forehead, pencil-thin moustache and sideburns. Good teeth.

He was wearing a shiny blue suit, pastel pink shirt and a tropical tie. All in all, he looked like a caricature car salesman. I must have seemed a little nonplussed; I guess I had imagined The Land to appear as a wise old Methuselah-type character in robe.

“What did you expect?” He asked. “This is your dream. So I can be a tree or a rock or a river if you’d prefer, but that would make conversation rather difficult, don’t you think?” Fair point.

“Anyway, this is my turn to be one of you humans, since one day you all come back to being part of me, part of The Land. Dust to dust and all that, eh?” He started to giggle, but I didn’t think it was all that funny. He had a boomy deep voice that didn’t gel with his spivvy appearance.

He pulled up a chair – an Eames Lounge Chair, I noticed with some surprise – and settled down into it with a sigh.

“The trouble with you humans” he said, “is that you look around, and see everything around you as other little people. You think everything’s got a personality, human desires and foibles. See – you’re doing it to me now in this dream!”

He leant back in his chair, his feet crossed on the ottoman. “According to you, it’s like the weather has good and bad moods, the plants have desires, you see faces in the clouds – and you even think that animals are your friends. Even cats!” This last word came out like a minor explosion. “And as for your gods: well you’ve even made them in your own image. ‘Uber-humans’ – just like people, only more so!”

I wanted to speak – I had burning questions like: “Where am I?” and: ” How much did you pay for that chair?” – but before I could get a word in, he continued:

“But that’s not why I got you here. Sit down, make yourself comfortable, I’m going to tell you a story.” I looked around, for the first time noticing (as you do in dreams) that we were in a huge empty hall, with black-and-white tiles chequered on the floor. There were no other chairs, so I just shifted my weight and folded my arms.

The Land smoothed down his moustache, apparently collecting his thoughts. “The story’s about Me. Apparently I’ve been around for 4.3 billion years. With a few hiccoughs, it all went pretty smoothly really, until just recently. You know: Earth formed, earth cooled, atmosphere, oceans, life – you know the plot. But it wasn’t ‘progress’ – that’s another one of your peculiar ideas, like ‘happiness’. It was just change, not heading anywhere in particular. Things were… well, just things, coming and going as things do.”

“And then you lot came along, writing and talking and talking and writing. Non-stop, changing everything that’s real in the world into a torrent of endless chatter. You’ve covered up the world with words. ‘Landguage’, I call it. ‘Textscape’. All your stories, your hopes, your plans, your petty miseries, all projected out onto me, till you can’t see me for all the jumbled layers of text. I look in the mirror and barely recognise myself anymore.” (But I recognised him: he looked just like the guy who sold me that P76 forty years ago.)

“But it’s not just the words, you know. It’s all the bloody pictures, too. For half a millennium you reckon you’ve been doing portraits of Me – drawings, paintings, etchings, photographs, you name it. Landscapes: ‘sublime’, ‘picturesque’, beautiful’- I should be flattered, but actually it gets right up My nose. My metaphorical nose, that is.”

“Because that’s not Me in all those pictures, you know. It’s you. More little people that you’ve created, this time on canvas, paper and screen. They say next to nothing about me, and everything about you. ##And that’s because – if I can pinch a quote from one of your better chatterers – ‘there is nothing either sublime or picturesque, but thinking makes it so’.”

“The fact is: “The map isn’t the terrain; and the landscape isn’t the land.“

With that, he paused, gazing abstractedly towards his feet on the ottoman. Then, with another sigh, The Land stood up, looking me squarely in the eye. I hadn’t said a word yet, but I had the feeling that our meeting was over.

“Oh, I nearly forgot – just one last thing before you go” he said. “Could I possibly interest you in a very fine pre-owned automobile?”