To the foreign observer, the Indonesian attitude to drug use may appear to be, well… inconsistent.

On the one hand, according to the World Health Organisation, there are 95 million ‘active’ tobacco smokers in Indonesia. Indonesian cigarettes are the cheapest in the world, mostly due to low levels of government taxation and regulation. Tobacco advertising and sponsorship can be seen just about everywhere you look. Attitudes to smoking are generally very relaxed (though this is changing, slowly), and there are very few public places where smoking is not permitted. It’s a huge and politically powerful industry, and the wealthiest individuals in the country are tobacco moguls (according the ‘Forbes Rich List’ 2018.)

In 2014, the National Commission on Tobacco Control stated that, nation-wide, 660 people die daily due to tobacco use.

At the other extreme there are, according to the national narcotics agency (BNN), less than 1 million people who are addicted to illegal drugs (‘narkoba’). A total of 4 million people are said to have tried illicit drugs at least once during their lives – with cannabis and amphetamine use being most common.

The BNN has estimated that, across the country, 33 people die daily due to use of narkoba. By a statistical coincidence, this is exactly 5% of the death toll from smoking.

But it is the use of illegal drugs that has been declared to be a ‘national emergency’. Capital punishment is in place for traffickers, and laudable (if occasionally hysterical) public health campaigns are in place to discourage illicit drug use.

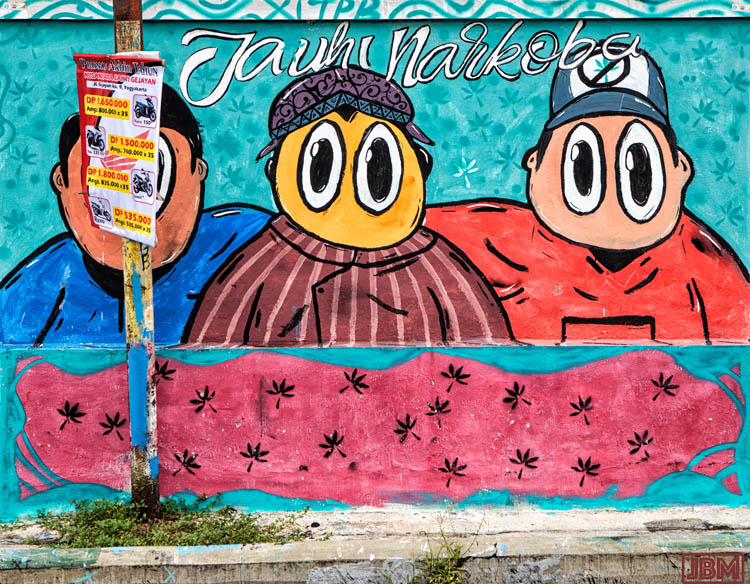

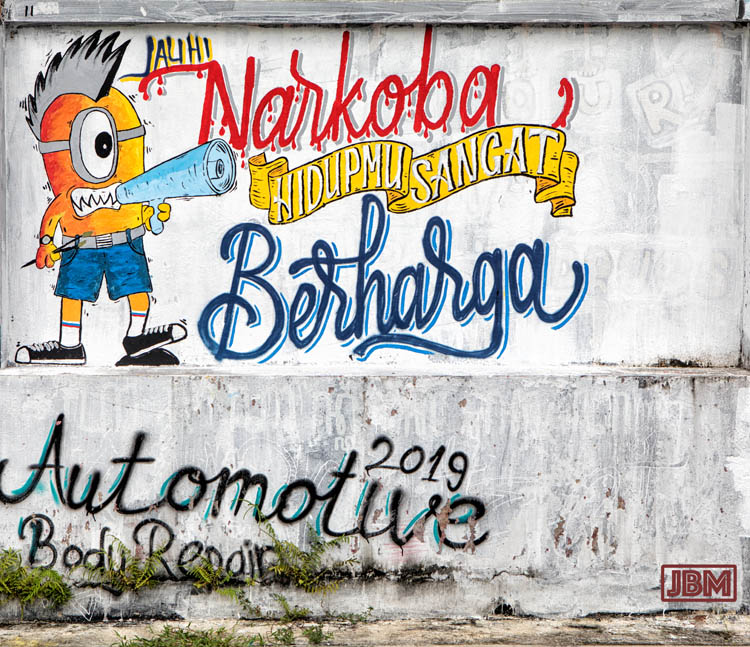

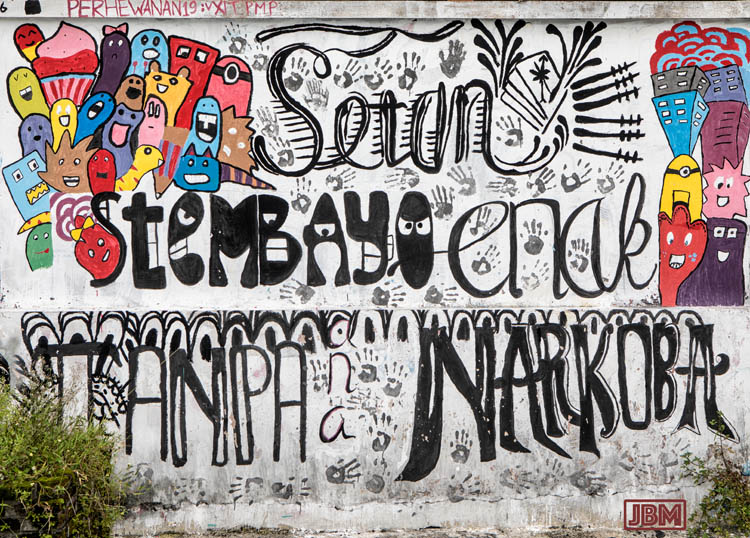

Here in Jogjakarta, there is a concrete wall running a couple of hundred metres along the length of Gang Gatotkaca. It marks the boundary of a large technical high school (SMK Negeri 2 Depok – Sleman). Students from each of the school’s subject divisions have painted anti-narkoba murals along the wall.

These murals are very creative – variously graphic, cartoonish, funny, clever, simplistic – and in some cases quite moving. Interestingly, like much of the ever-present tobacco advertising billboards, many of the messages are spelt out in English.

I photographed them when we were last here, back in November 2016. But they are still there, their messages just a little faded.

Napza [Narkotika, Psikotropika dan Zat Adiktif lainnya] No Thanks. Stembayo sembada tanpa narkoba

“Drugs? No thanks. STEMBAYO [the former name of the school] is good/capable without drugs”

Peringatan: Narkoba membunuhmu

“Warning: Drugs kill you” [paraphrases the warning now printed on cigarette packets and advertisments]

Bentengi dirimu dari narkoba

“Fortify yourself from drugs” [Note the inclusion of ‘rokok’ (cigarettes) in the display]