Last month we made a very interesting 10 day journey up-river from here, into the district (kabupaten) of Gunung Mas (literally, ‘Gold Mountain’). We wanted to visit three famous betang (longhouses) – at Tumbang Korik, Tumbang Anoi, and Tumbang Malahoi. We wanted to see how much primary Borneo forest can still be found up around the headwaters of the Kahayan and Rungan rivers, close to the ‘heart of Borneo’ (The short answer? Much less than we’d hoped for).

But first, we wanted to attend another Dayak Tiwah funeral ceremony at Kuala Kurun (the capital of Gunung Mas), the key days of which coincided with our visit.

Every Tiwah we’ve attended (this was our fifth so far) has had the same basic purpose. That is, to send the souls of one or more deceased people on their journey through the Upper World to the ‘Prosperous Village’ of Lewu Tatau, and to help them on that journey. Many of the complex ritual practices, derived from the Kaharingan religion, have been (almost) the same in each Tiwah. However, in other ways each Tiwah has been different, with special and unique features.

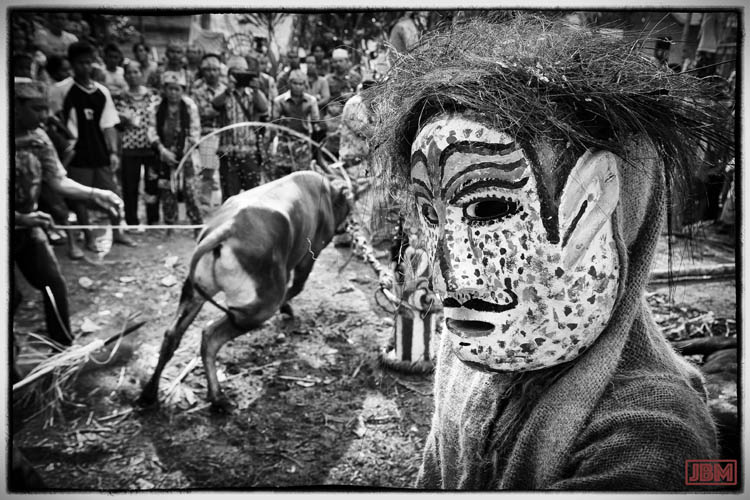

In Kuala Kurun the really outstanding features were the bukung figures (like the one in the above photo) and the Laluhan – arrival of visitors from the village of Petak Bahandang on board a massive bamboo raft. I’ve written about the bukung previously.

We arrived just as the central area of the Tiwah was being prepared. The sankaraya, with its bamboo poles, brightly coloured flags above and offerings below, was erected. Two large sapundu had been carved from kayu ulin (Borneo ironwood) and painted. Each was carried in on the shoulders of a group of men, who then placed it in a hole and secured it upright. It needs to be secure, as this is where the buffalo are tethered and sacrificed.

This Tiwah was a ‘secondary funeral’ for six people who had passed away during recent years. Their remains were exhumed from their graves, the bones cleaned, then re-interred in family ossuaries, known as sandung. Each wooden sandung may contain the bones of a number of related family members, sometimes spanning a number of generations. But at this Tiwah, at least one of the sandung was new, so new in fact that it was still being carved and constructed during the Tiwah.

In the photo above, the framework of the sandung can be seen behind the craftsman, who is carving Dayak motifs into one of the side panels. He first draws the designs onto a sheet of paper, then cuts out the template and traces the design onto the timber before carving.

He was also finishing work on carved human figures, animals and objects that would adorn the supporting pillars of the sandung. All are constructed of kayu ulin, timber of the Borneo ironwood tree, which has spiritual power for the Dayaks, as well as practical attributes of being resistant to weather, insects and fungi, hard and strong, and with fine even grain much favoured by sculptors and carpenters. Unfortunately it’s also very slow-growing and has nearly disappeared from the forests of Kalimantan.

As a large and important Tiwah, there were no less than seven basir in attendance. These men (and they are always men) are experts in the complex rituals of the Kaharingan religion, its prayers and chants, all conducted in the sacred Sangiang language, which is only ever used during Kaharingan ceremonies.

Each of the basir accompanies his singing/chanting/praying by playing a special little drum (katambung). Each sits with his feet placed on a gong. Their ‘songs’ (prayers?) have a slightly hypnotic repetitious structure, and are mostly fast paced, and pleasingly melodic. The basir seated in the middle would lead off with a verse – the precise melody of which would vary according to the number of syllables in it – and the three other basir on each side would respond with the chorus in unison. Some songs contained dozens of ‘verses’.

The katambung are themselves quite beautifully made and engraved. Like the bronze gong, they are imbued with spiritual power for the adherents of the Kaharingan faith. (At another time I’ll write about a visit we made to a gong foundry/workshop).

In front of the basir are placed many offerings to delight the spirits and entice them to descend to the Tiwah. Amongst the offerings above are hornbill feathers, uncooked rice, cigarettes, money, bowls with blood of sacrificed animals (chickens, pigs, cows and buffalo), rice wine (baram), flower petals, and sirih – consisting of betel leaf, areca nut and slaked lime (calcium hydroxide).

The case of Bintang beer in the background is not there for the spirits to consume.

Outside, two buffalo were tethered to the sapundu with a halter and rope made of rattan. The animals’ horns and tails were decorated with ribbons and coloured fibres, and they were given plenty of tasty fodder and water. Their spirits need to be in good shape so that they can accompany the souls of the deceased humans on their journey to the ‘Prosperous village’ of heaven. But we imagined that the poor beasts were somehow aware of the fate that awaited them the next morning.

As always at a Tiwah, almost everyone joined in the Ngangjun (called the Manganjan on the Katingan River), a sort-of-a dance where a circle of people proceed anti-clockwise around the sankaraya, and the sapundu where the buffalo stands. They move slowly to the sound of the gongs, raising and lowering their arms as one, then taking one step to the left and repeating. In the night, with just a few sources of illumination, it was quite beautiful.

The next day was Tabuh 1, the biggest day of the Tiwah, beginning shortly after dawn with the Laluhan – the arrival of guests from the downstream village of Petak Bahandang. These villagers came with gifts of food, money, rice wine etc, in response and gratitude for similar assistance provided to them several years earlier during a Tiwah of their own.

Dozens of them arrived on board a large bamboo rakit raft constructed specially for the occasion, brightly adorned with flags attached to long bamboo poles. The whole thing was towed up-river by two klotok (motor-powered longboats). Bukung figures buzzed around the rakit on other klotoks, and the whole procession did three circuits up and down the river before coming in to the docking platform.

On the floating dock, basir and senior community leaders waited to greet the arrivals. In the middle stands Pak Bajik Simpei, who turns out be the father of Yoppie, one of Karen’s workmates at the Museum Balanga in Palangkaraya. They stood armed with mandau sabres, spears … and handphones and video cameras.

As the rakit pulled in to the floating dock, there was loud gong music, and firework rockets sounded almost continuously. Buckets and hoses were used to spray people on both sides, and volleys of straight branches (of kayu suli) were thrown, spear-like, towards the people on the raft. It was a mock battle – but conducted with great good humour (and without injury.)

The whole crowd then surged up the narrow laneways to the place where the Tiwah was being conducted. (Can you spot Karen?)

At the Tiwah grounds, there was a gate with a log (pantar) across it to prevent their entry. They were questioned about their purpose in coming to Kuala Kurun, and their leaders spoke (eloquently, it would appear) about their gratitude for the help provided to them during their own Tiwah, and their earnest desire to reciprocate. The speeches were clearly warm and heartfelt on both sides, and there were some tears.

They were allowed to chop through the barrier log with a mandau, and all entered, accompanied by much consumption of baram rice wine – and shot glasses of spirits (Johnny Walker!)

Inside the Tiwah grounds, everyone (the two bule foreigners included) received a liberal pasting of talcum powder to their cheeks. We are not sure of the purpose of this (which has occurred at other Tiwah also), but it does look rather fetching don’t you think?

Then the crowd gathered, handphones at the ready, for the sacrificial spearing of the buffalo (kerbau). We stood on the back of a 4WD utility belonging to the Bupati (the ‘regent’ of Gunung Mas district) to get a better look at the throng.

The actual killing of the kerbau (as well as a number of pigs and chickens) was done mercifully quickly.

Bowls of fresh blood were added to the other offerings. Blood of sacrificed animals is regarded as cleansing and a symbol of life-force and strength.

The urn on the right of the photo above is a balanga. These jars are highly valued, and may be passed down through generations as family heirlooms. Some balanga are regarded as possessing great spiritual power, and may even be dangerous. Most were originally made in China or Vietnam (though in later years they have also been made by Chinese pottery businesses in northwest Borneo). They were traded repeatedly, and can be found in some of the most remote villages in the very heart of the island of Borneo. Dayak people may be unaware of their Chinese origin, and consider them to be ‘divine jars’.

The songs and prayers of the seven basir resumed, with a special session to thank bestow blessings onto the visitors from Petak Bahandang village.

The mood was warm, friendly and celebratory, as it was throughout the parts of the Tiwah that we witnessed (the full ceremonies went on over a period of three months!) Liberal distribution of baram and Bintang beer (as above) probably helped.

A Dayak funeral is not an occasion for grief and mourning; this is partly because the Tiwah may occur months (or even many years) after the actual death, but also because the spirit of the deceased may not want to leave the village on its journey to the Prosperous Village of Dayak heaven if it sees family members unhappy.

The Tiwah ceremonies continued over subsequent days, but we headed off by 4WD and klotok canoe to the villages up near the headwaters of the Kahayan River. But those stories can wait for another time…