The traditional ancestral house in Toraja, South Sulawesi, is known as a tongkonan. The name means ‘a place to sit’, because the tongkonan is the place where family and broader community members gather and meet.

Unlike a lot of vernacular architecture around the world (such as the longhouses of nearby Kalimantan), these remarkable ‘saddleback’ buildings are not disappearing from the countryside. On the contrary, the large tongkonan, along with the smaller but very similar-designed rice-barns (known as alang) are seen dotting the landscape almost everywhere.

And new ones continue to be built, too. They have undergone a resurgence in cultural significance, both as iconic symbols for the region’s tourism industry, and more importantly as a powerfully distinctive symbol of Torajan cultural identity.

We slept a couple of nights in the tongkonan on the left in the picture below (in desa Sa’dan Ulusalu).

In the 1950’s and 60’s the central government had sought to suppress the construction and use of tongkonan which they viewed as ‘backward’ and ‘primitive’. However they have since come to see their value for tourism, and as a ‘safe’ token of ethnic diversity in Indonesia. Other public buildings, businesses and even churches are now often built to reflect the traditional form of a tongkonan.

In times past, only families of the nobility were permitted to construct a tongkonan, but that rule is nowadays relaxed. This is in part due to the diaspora of Torajans across Indonesia, sending remittances home to their families. Families who may have been at the lower end of the social hierarchy now have enough money to build their own tongkonan. The change is also due to the powerful Torajan church wanting to break down the previously very hierarchical nature of society, and promote greater equality.

We’ve heard three different explanations for the origin of the distinctive tongkonan shape:

1. The first is that the people of Toraja came by boat from mainland Asia, and their boats were then used for shelter. As new homes were constructed, they retained the boat-like form.

2. The second story is that the shape is that of a building in heaven, which was mimicked by the Torajan ancestors when they came down to earth.

3. The third explanation (which I rather like) is that the upswept roofline is intended to resemble the shape of buffalo horns – as buffalo (kerbau) are very significant and deeply symbolic in Torajan culture.

Both tongkonan and alang are always aligned along a north-south axis, with the tongkonan facing northwards and the alang opposite and facing south. They form two neat rows when built en masse.

They stand on piles, so with the vaulted roof on top, they contain three distinct levels – symbolic of the three levels of the universe in Torajan cosmology. The attic level is where family heirlooms are housed. The living area is on the main level, accessed usually through a doorway at the north end of the east wall. The area underneath may be partially or fully enclosed, and can be used to house domestic animals or for general storage.

We were told that the construction of tongkonan is a very specialised skill, and that the builders/artisans who construct them all come from just a few villages in the region. That’s not difficult to believe, as the process appears to be both technically complex and perilous. For instance, they were (and possibly still are) constructed without any use of nails or screws.

And just take a look at the very lengthy bamboo poles and scaffolding propping up the roof as it is being built – and the ‘protective footwear’ worn by the builders.

An average-sized tongkonan can cost around Rp700 million (a little under AU$7,000 at current exchange rates). Given that one ‘very special’ buffalo (e.g. a blue-eyed albino with particular auspicious markings) can cost almost as much, the price of a new tongkonan seems quite reasonable. A team of ten will need about three months to build it, and a further month for the external carving and decorations.

We attended a ceremony in the village of Patongko to inaugurate a newly constructed family tongkonan. Like a Torajan funeral ceremony, this was a massive, multi-day affair, with hundreds of attendees, including family members who returned home from all over Indonesia for the occasion. Active participation in ceremonies like this is essential for anyone wanting to maintain their connections to family and its tongkonan, and their place within the family.

At the front of the new tongkonan were three bamboo frames decorated with masses of fine textiles and cordyline leaves.

As with funerals, a number of temporary buildings and shelters were specially constructed using bamboo for the formwork. After the ceremony, all these constructions were to be demolished and burnt or re-purposed.

There were also a large number of animals sacrificed at the ceremony. As wells buffalo, there were some 98 pigs, mostly donated by family, friends and neighbours. Ahead of their terminal contribution to the proceedings, the condemned pigs were housed and displayed in bamboo enclosures, arranged around the new tongkonan.

Children brought them water and leafy snacks to ease their discomfort.

The roof of the tongkonan is traditionally built from layers of split bamboo. Nowadays it will usually be topped with sheets of corrugated iron. Less attractive – but more durable…

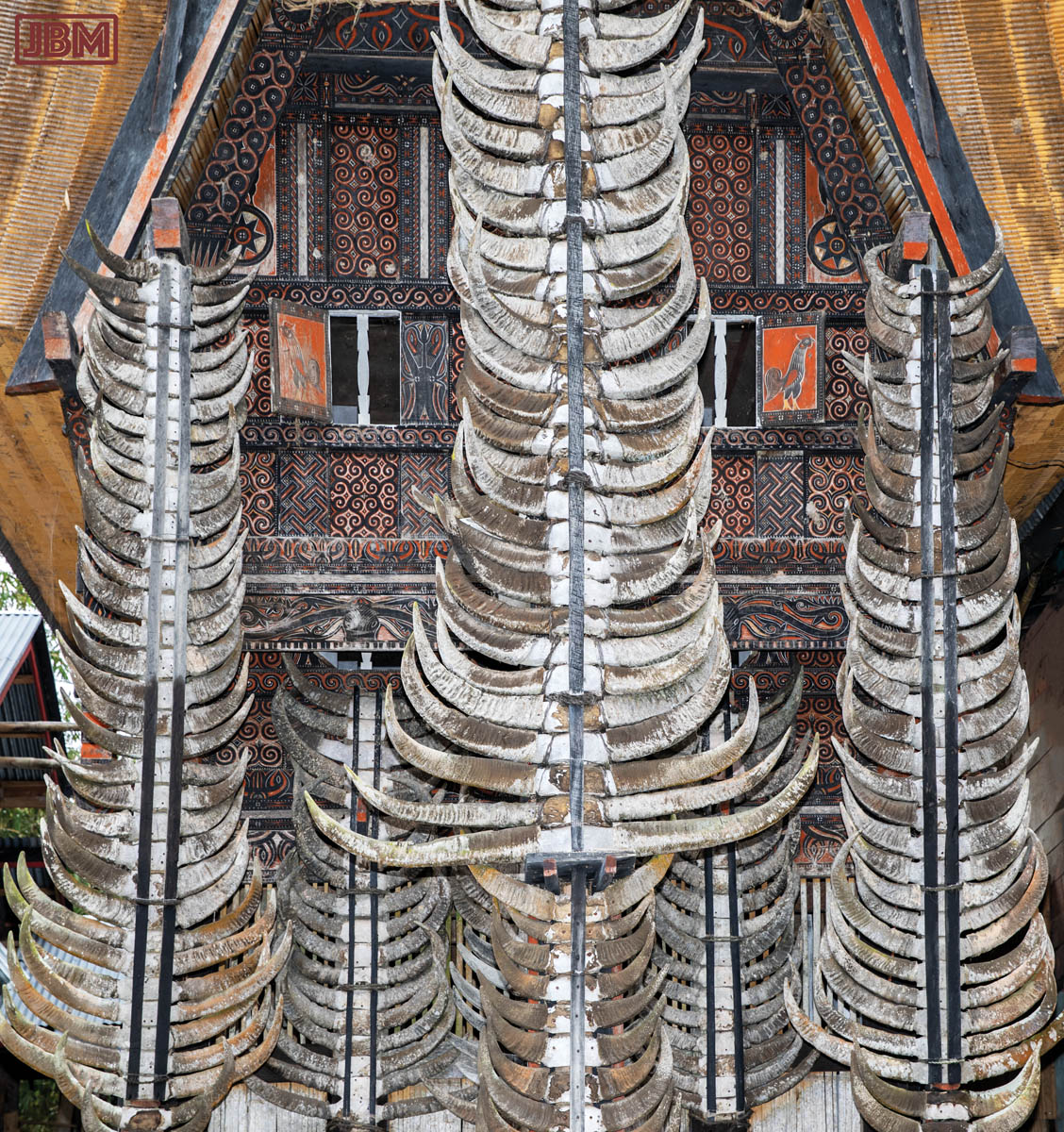

The external walls are usually (but not always) ornamented with carved designs, hand-painted in red, black, yellow and white. Motifs represent the sun and moon, buffalo, buffalo horn, roosters, and a knot or basket design.

The front (north-facing) end of the tongkonan (but not the alang rice-barn) is usually adorned with a stacked array of buffalo horns. Collected from buffalo sacrificed for funerals and other ceremonial/ritual occasions, they symbolise prosperity and strength. Considering the often exorbitant price of buffalo in Toraja, an array like this is certainly an indicator of considerable wealth!