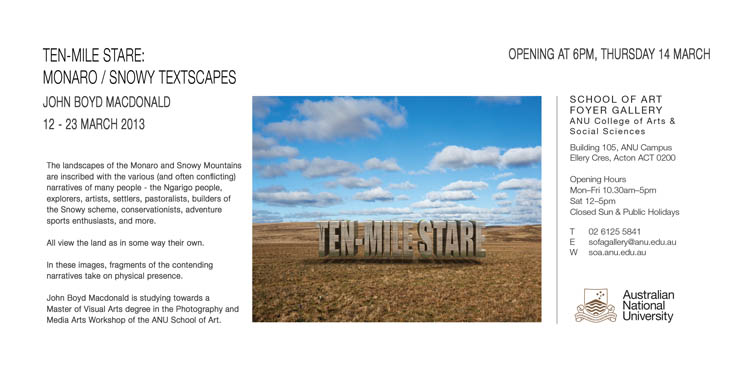

My new photographic exhibition (Ten-Mile Stare: Monaro / Snowy Landscapes) will be at the Foyer Gallery, School of Art, at the Australian National University. 34 framed images of Monaro and Snowy Mountains landscapes, incorporating text expressing a range of different interpretations of the land.

The work will be on show from 12 to 23 March, with a GALA OPENING at 6pm on Thursday 14 March.

All works are for sale, and a book of reproductions (also containing notes about the images) is also available. But admission to the exhibition is free, so just come along for a look!

You can preview the images in the show here.

About the images:

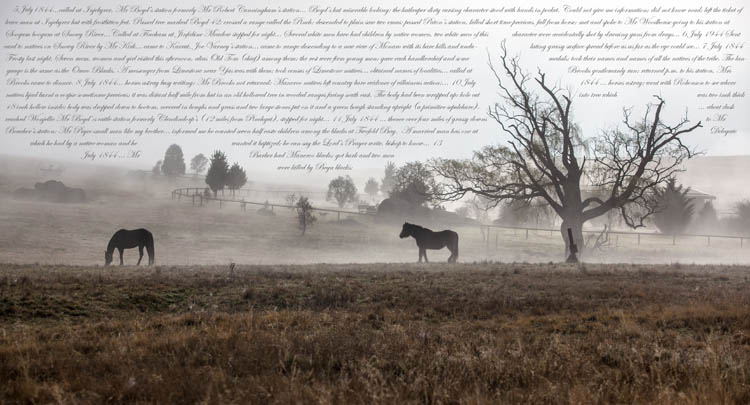

The Monaro and Snowy Mountains regions of New South Wales are home to a diverse range of radiant landscapes. From the rolling treeless plains of the Monaro to the herbfields, snow and granite tors of the ‘High Country’, there are countless views to satisfy anyone in search of the picturesque and the sublime. These are landscapes that reward slow and extended examination. The back roads and backcountry hiking trails reveal serendipitous splendour, and the regular visitor sees a landscape that transforms with the seasons.

But these are places that mean different things to different people. Multifarious layers of identity have been written onto the land. For millennia it was the country of the Ngarigo people, and was also visited and/or occupied by people of the Walgalu, Ngunnawal, Yuin, Bidawal and Jaithmathang.

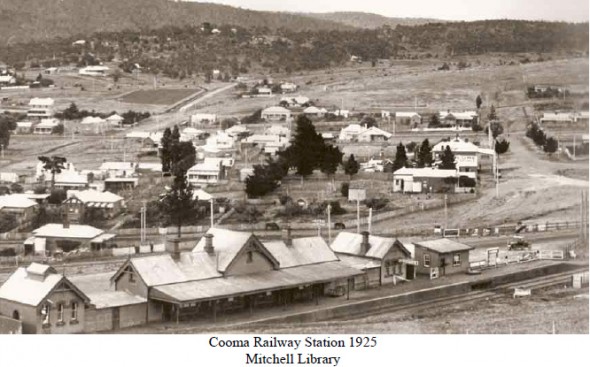

Since the arrival and occupation of the land by Europeans from the 1820s, there have been explorers, squatters, convicts, settlers, gold miners, merchants, bushrangers, pastoralists, townsfolk, dam-builders, adventure-seekers, conservationists and artists. Each has brought their own narratives, their own plans, dreams and visions – and often even brought their own place-names. Their various narratives, names and interests have contested for dominance ever since, sometimes in open conflict. This process continues.

And, of course, I also bring my own narratives. In 1835, my great-grandfather was assigned as a convict to a station at the northern end of the Monaro. For 40 years from the 1890s my grandfather held summer grazing leases up near Mt Jagungal, and my own family farmed on the western side near Tumbarumba. Nowadays I frequently travel from my home in Canberra to the Monaro and Snowy Mountains, to bushwalk, tour and make photographs.

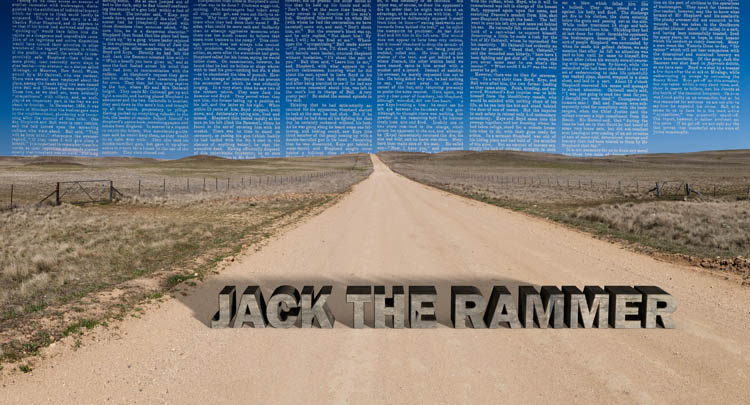

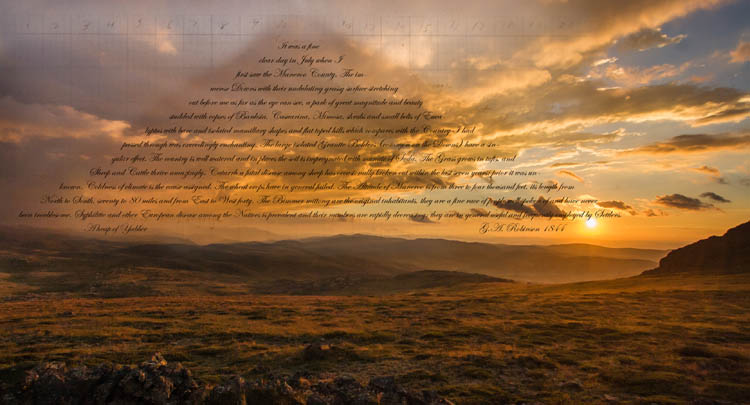

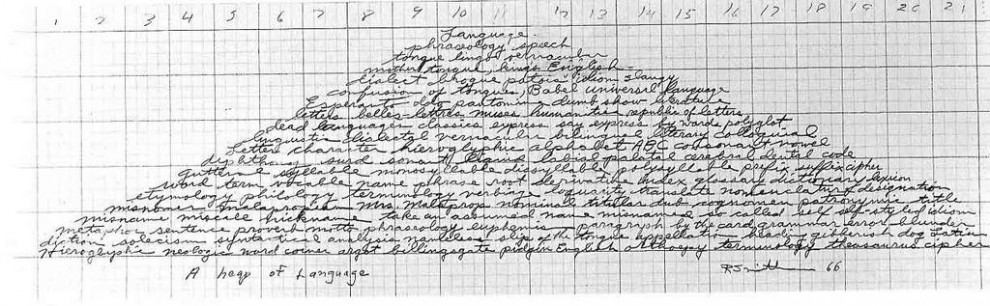

In these images I have tried to express, hopefully without judgment, some of the contending visions of this glorious land. These take on physical form as text-objects, placed or projected onto the topography. They aim to appear as real and as solid as the features of the landscapes that contain them. Their meanings range from the obvious, even clichéd, to the more obscure, allowing for multiple interpretations.

I prefer to think of them as images rather than photographs, because they are manipulated and contrived, and also because they only partially aim to serve as representations of the ‘real world’.

And not landscapes, but textscapes, as I am interested in what the addition of text does to our viewing of a photograph. Although starting out as picturesque views of particular ‘rural’ and ‘wilderness’ landscapes, these images aspire to become fields of meaning.