Banjarmasin is the capital of South Kalimantan (Kalimantan Selatan, usually just referred to as ‘KalSel’).

It likes to promote itself as “The Venice of the East”. The Lonely Planet reckons this is “a jaw-dropping exaggeration”, saying that the city “sprawls in all directions but offers little”.

Well, sorry Lonely Planet, but we beg to differ. We’ve now been there on five occasions, either visiting or passing through, and have found that it’s got its own distinctive character and appeal, and doesn’t need a pointless comparison with Venice!

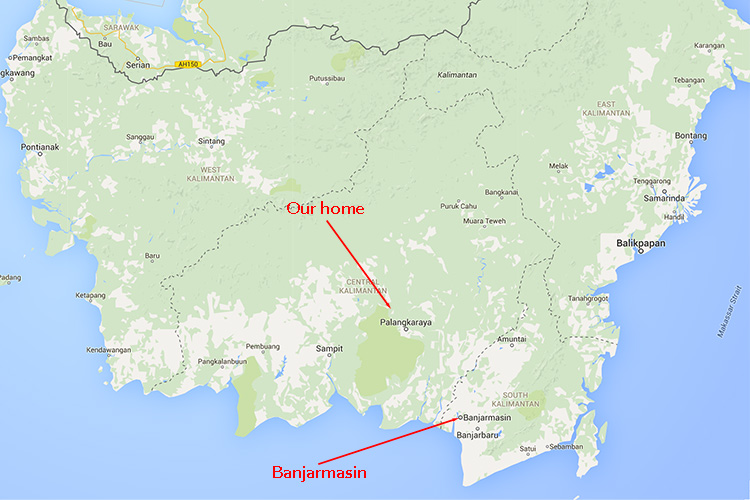

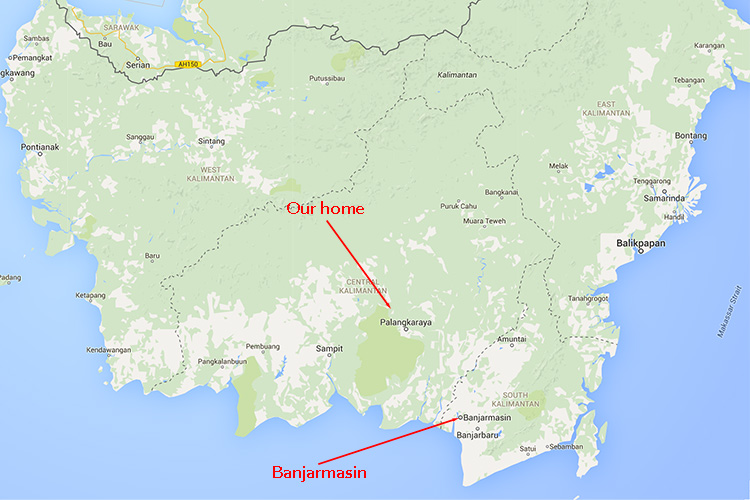

Banjarmasin sits at the confluence of the Barito and Martapura rivers. It’s around six hours’ drive by car from our home, which is north of Palangkaraya in the neighbouring province of Central Kalimantan.

‘Banjar’ is a port city, and it’s the centre of commerce and industry for the province – which is actually one of the wealthiest (at least in terms of exports) in Indonesia. It was the capital of the Dutch colonial administration in Borneo, and after Independence it was the capital of our own region, until Central Kalimantan split off to form its own province in 1957.

Officially the population is a little over 600,000, but when you combine the cities of Banjarmasin, Martapura and Banjarbaru which are run into each other, there’s a total population of well over a million.

The best way to see Banjarmasin, and to experience its friendliness, is to leave the roads behind, get into a small boat and get out onto the complex maze of rivers and canals, massive, mid-sized and minuscule, that criss-cross the city.

A large proportion of houses back (or front) onto a waterway, and riverside is probably the more important side. It’s where you bathe, clean your teeth, wash and dry clothes. It’s where your children play, you catch fish for dinner, grow a few potted plants, relax and socialise.

The waterways are also a place of commerce, and the early morning fruit and vegetable markets are still going strong in places like Lok Baintan. The Pasar Terapung is held every morning, with sellers (and most buyers) doing business from on board their little canoes.

The range and quality of produce was good, and the prices seemed alright too. They were selling local seasonal fruit – mangoes, bananas, guavas, wild mangosteen, kasturi (Kalimantan mango), and some green vegetables. The fruit was carefully and nicely presented, in woven baskets or colourful plastic containers.

Before I make it sound idyllic, I should mention that the waterways can also be… filthy. As well being the used for transportation, catching fish, bathing and washing clothes, they are also used for disposal of household garbage and human waste (with only 4% of households connected to the new sewerage system). Everyone just relies on the tides and the flow of the rivers to flush everything away downstream to the ocean and out of sight.

Such a system might once have worked satisfactorily, when the population was a tiny fraction of what it currently is (it’s grown by 1000% in the past century), and when most of the garbage was organic and biodegradable. But now there’s a huge volume of inorganic waste (especially plastic and foam packaging), and the environmental impact is all too obvious.

The Barito River provides a deepwater port, and the main point for entry of manufactured goods and imported foodstuffs to South and Central Kalimantan.

It’s also a point for transfer of goods between the the river traffic from up-river and the inter-island and international vessels. There are two main kinds of outward-bound bulk freight: coal and timber.

Huge amounts of coal are mined in the northern and eastern parts of South Kalimantan. The industry has expanded greatly in recent years, and the province now produces around one-third of Indonesia’s coal (with most of the rest coming from adjacent East Kalimantan). Incidentally, Indonesia has advanced to now be the world’s 5th largest producer of coal (Australia is No 4).

Legal coal concessions in South Kalimantan now cover around 1 million hectares (over 25% of the total area, including 14% of the forests). The environmental impact of the coal industry is felt not only in the areas of the open-cut mines themselves, but in pollution of the downstream river systems – and eventually of course in the increased CO2 emissions from burning all that coal. (Greenpeace have recently published a detailed report on the coal mining industry of South Kalimantan).

Most of the coal gets trucked from the mines to the river, and then loaded onto flat-bottomed coal barges which are then towed down-river to Banjarmasin. The barges are massive things, black floating mountains.

Timber production in South Kalimantan has reportedly declined since its peak in 1998, due mostly to the depletion of forests and the failure to establish large-scale productive plantations. (Logging continues largely unabated in the other provinces of Kalimantan.)

But based on what we saw, there’s still an awful lot of big-tree timber being floated down the Barito to Banjarmasin for processing and/or export. We were told that much of it comes from ‘our’ province of Central Kalimantan.

There’s a stretch of several kilometres along the river that is entirely given over to sorting, storing, loading and processing of logs from upstream. In places, the waste timber and bark forms expanses of reclaimed land sticking well out into the river.

It’s a strange landscape. It’s all timber but it’s treeless, with clouds of smoke and people working ant-like amongst the logs, cut timber and the ‘waste’ wood and bark.

Along another stretch of the east bank of the river is a neighbourhood of Alalak, where the boat-makers have their businesses. The large boat on the right of the photo above was virtually finished, and the builder (the man sitting in the middle) said that he expected to sell it for around Rp17 million (around AU$1700).

The population of the city is 96% Muslim, and there are over 1000 mosques. By far the largest is the ‘Grand Mosque’ of Banjarmasin – the Masjid Raya Sabilal Muhtadin – which is one of the largest in Indonesia. At Friday prayers there is room for 5000 (men) inside. Construction was completed in 1981. We were told that the site, on a prime location in the middle of town, had previously been earmarked by the Dutch for construction of a cathedral, but they never got beyond putting down the foundations.

Nearby Martapura is considered to be even more devout, with so many Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) that it is known as kota santri (the city of students), or even as ‘the verandah of Mecca’!

The Masjid Sultan Suriansyah is much smaller, but is revered as the oldest mosque in South Kalimantan, 300+ years old.

The soils around Banjarmasin are quite fertile (especially when compared with the barren sand and peat soils of Central Kalimantan), and they produce good quantities of rice there. It’s wet-rice cultivation, unlike the less productive, slash-and-burn, dry rice ladang cultivation of the Dayaks in our area.

There is a diamond mine at Cempaka, about 10 km from Martapura. They’ve been finding diamonds, and processing all sorts of precious and semi-precious stones in this area for hundreds of years. Cempaka diamonds are quite famous, but the mining processes are still very rustic, even basic, and entail men spending a lot of time standing waist-deep in mud and muddy water, pumping sludge up through pipes to be sifted for diamonds. It’s a process much like that used to dredge for gold in the rivers of Central Kalimantan.

We were told that the men refer to the diamonds as ‘galah’ (meaning ‘princess’ in bahasa Banjar) and avoid using coarse language while they work, in the belief that the ‘princesses’ will hide from them if they do.

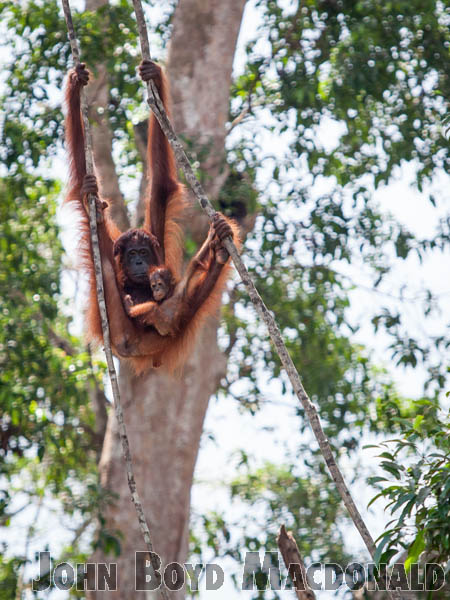

And, speaking of princesses…

There’s a lot more that could be said about Banjarmasin. Architecture, for instance – or history, as Banjarmasin has been at or near the centre of Borneo affairs since well before the arrival of Dutch spice traders and colonialists.

Or food. A whole book could be (and probably has been) written about Banjar food – especially my favourite, the delicious lime-and cinnamon tinged soup called soto banjar. Unsurprisingly there’s a lot of fish, prawns, squid and other seafood and river fish on the menus. The best places to eat are local restaurants like the Bang Amat (for soto banjar) or Cendrawasih (for barbecued seafood).

Perhaps I’ll write at another time about food specialities of Kalimantan.

Till then, Happy New Year to all! We’re heading off north in early January to visit some villages in Gunung Mas and Murung Raya regencies. We plan to see some ‘classic’ longhouses, learn a little more about Dayak culture, and (hopefully) encounter some primary forest in ‘the Heart of Borneo’. Whatever happens, it’s bound to be full of interesting surprises…