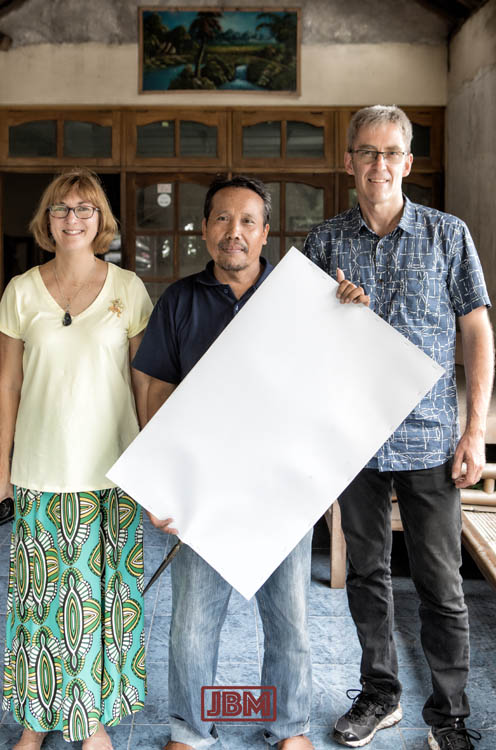

During another very enjoyable month in Jogjakarta, we went away for one extended weekend to visit the city of Semarang, located on the north coast of Central Java. We were in great company, accompanied by Kadek and Roro (who are, in equal measure, our guides, teachers and friends) and by Martine and Juris (who are fellow volunteers, fellow students – and also friends). It turned out to be (as always) an interesting and rewarding excursion. Here’s a few highlights…

Our drive up there skirted around several volcanoes, including Merapi and and Merbabu.

Semarang is the fifth biggest city in Indonesia (after Jakarta, Surabaya, Bandung and Medan). Although the city proper ‘only’ has a population of 1.8 million, the greater urban area totals around six million. We arrived at the start of a long weekend, and it seemed like all six million of them were on the road. (Yes, those balloons are on a motorbike.)

There is a sizeable Chinese Indonesian community in Semarang, and a number of examples of Chinese architecture, and not just in the ‘Chinatown’ area of town. The Sam Poo Kong temple dates back to the beginning of the 15th Century CE, when the Chinese Muslim explorer Admiral Zheng He visited the area. He (He) prayed in a little cave, and a small temple was established on the location. It is now a site used by people of various faiths – Confucian, Muslim, Buddhist and Hindu, while retaining a very Chinese feel to the architecture and artworks. Over the centuries it has endured many cycles of neglect and renovation, and was restored to its present impressive condition just ten years ago.

The Tho Tee Kong temple (also called Dewa Bumi) is used by people praying to the earth god Tu Di Gong – who will “provide fertile soil, abundant harvest and a wealth of natural resource diversity”.

The temples (klenteng) have all been built around a central paved square. One one side is a large stage area, used for all kinds of performances and ceremonies. While we were there, a large team of young Danish gymnasts arrived to put on an acrobatic show for the bemused locals.

We visited each of the temples on site, attracting some curious glances, and (as always) great interest from the children.

When we arrived at the Klenteng Tay Kak Sie, preparations were under way for a ceremony to mark the seventh anniversary of the death of prominent member of the community. A model house, complete with cars, staff, air conditioners, satellite dish etc was constructed, all from paper, to be burnt later that day. Meanwhile temple attendants prepared an elaborate meal for the spirits.

An oil flame candle burnt in a bowl beside the shrine.

In another part of the temple are shrines for several bodhisattvas and guardian deities – this one to the ‘minor’ Taoist god Kong De Zun Wan (known in Hokkien as Kong Tik Djoen Ong).

Displayed in alcoves along one wall are engraved tablets dedicated to the memory of prominent members of the community.

Not far from the Klenteng Tay Kak Sie is Kota Tua, the old Dutch centre of town, with a number of fine (and not-so-fine) examples of colonial architecture. (The centre of town has long since moved to another area, which is less prone to flooding.) The Immanuel Protestant Church of Western Indonesia (generally known as Gereja Blenduk) was first built in 1753, and is the oldest church in Central Java.

Beside the old church is a little lane lined with about a dozen stalls. They call it an ‘antique market’, but in reality it’s a wonderfully eclectic mix of genuinely old stuff, artwork of variable quality, broken and/or obsolete equipment (anyone need an instamatic camera or a Gestetner machine?), quirky oddities – and some tacky junk. All set out against a backdrop of attractively run-down warehouses and offices. All very photogenic…

These old cameras are now mute (they’re cameras, after all…) but, if they could speak, I’m sure they’d have many interesting stories about the exotic scenes they had captured…

We have developed quite an interest in children’s games and toys in Indonesia, with many traditional games (e.g. kite-flying, spinning tops) still very popular. Karen was delighted by these little toys, which may be unique to this area (Does anyone know more about them? The stallholder himself did not know much). You wind a piece of string around the wheel, and the figure is somehow propelled forwards when you pull on it

The owner of this stall seems to have made a point of hanging a printed photo of former President Suharto beside another of Hitler and Mussolini. ‘Old Order’ and ‘New Order’?

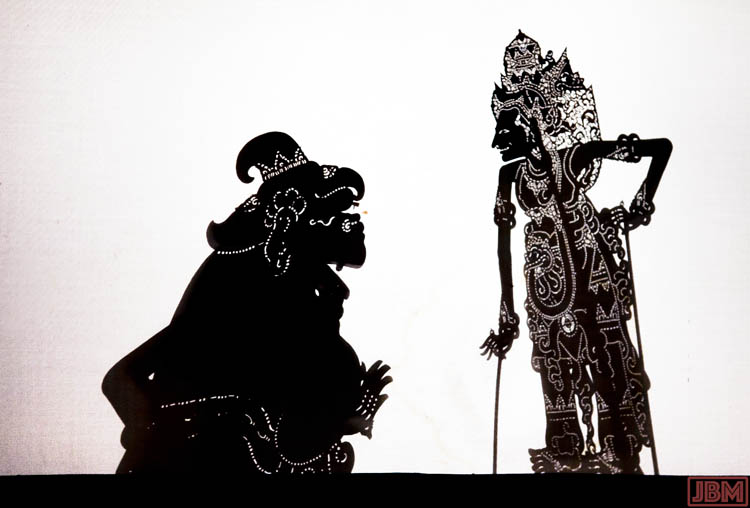

Another stall had a great mingling of European ceramics and Javanese statues and other artworks. The four figures above would be immediately identifiable to any local. They are Semar, Gareng, Petruk and Bagong – the four Punakawans who are only found in the Indonesian version of the Mahabarata epic. They appear clownlike, but they are themselves gods, and are deeply profound observers of human folly – especially Semar (on the left in the photo above) – who is the father of the others.

After a rather nice seafood lunch at the local branch of the Rumah Makan Cianjur franchise we went to visit the Lawang Sewu. This compound of four elegant white colonial buildings is the former headquarters of the Dutch East Indies Railway Company. In the Javanese language, Lawang Sewu means “one thousand doors”, and there certainly are a LOT of them – though perhaps not quite 1,000! The central courtyard is adorned with frangipani trees and one huge and very old mango tree.

Construction of the complex began in 1904, in an architectural style known as ‘New Indies’, apparently a version of Dutch Rationalism, transitional between 19th century classicist and the modernist styles of the early 20th century.

The Japanese occupied the building during the 2nd World War, and used the basement of one building as a prison. Several executions took place there. Later in the war there was a battle between Dutch and Japanese troops in the tunnels below the building, in which many died. As a result of this history, the building has a strong reputation for being haunted, including by at least one headless spirit. (Indonesians seem to commonly believe in ghosts, and enjoy being terrified of them!)

The basement is closed off at present, supposedly for renovations, but I got at least one ghost photo upstairs (who bore a striking resemblance to our friend and fellow volunteer Martine!)

A nearby church spire viewed from the top of the Lawang Sewu.

Along the lane of the Kota Tua ‘Antique Market’.

Street art on a wall near Lewang Sewu.