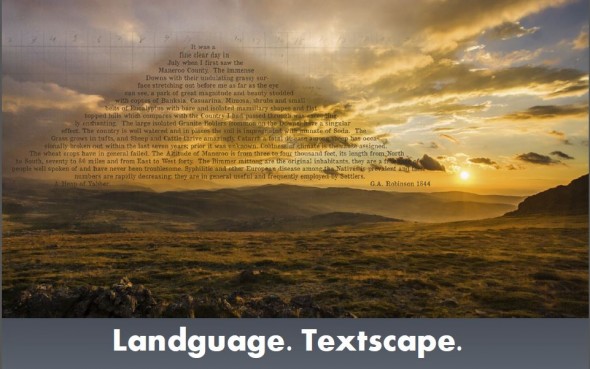

The Dutch said it first. Around 1500, they began to use the noun landschap to describe a new kind of artwork depicting ‘natural inland or coastal scenery’. It spread to use in other Germanic languages (e.g. as lantscaf, landschaft, landskap), and appeared in English (first in the form of ‘landskip’), by the 1590s.

Land is, unsurprisingly, an ancient word. It was used (in the form of londe) by the Venerable Bede, and its form varies little across the Indo-European languages, indicating much older and deeper roots. The –scape part has the same etymology (according to the OED) as the noun ‘shape’, meaning form, condition, or configuration.

But in contemporary usage, landscape has acquired additional meanings. It is used to denote a tract of land, to refer broadly to the visual environment and, through combination with adjectival qualifiers, we speak of ‘urban’, ‘natural’, ‘political’, ‘intellectual’ and other landscapes. As a verb, it refers to altering or shaping the land. My interest, however, remains with its original application i.e. to visual art.

Giorgione. La Tempesta (The Tempest), c1506. Oil on canvas.

“The first landscape painting”?!

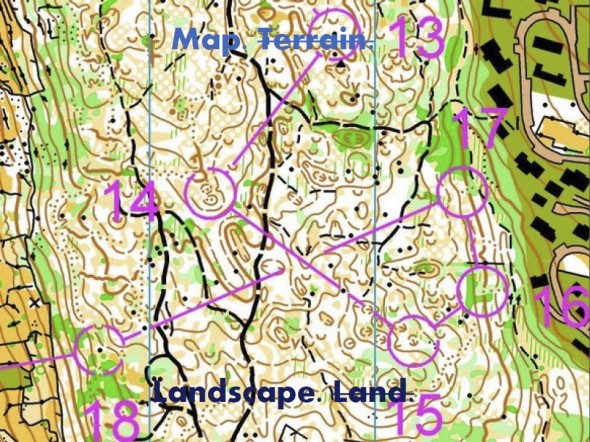

It’s a fuzzy word. Its meaning shifts according to usage, causing it to carry tones of other, closely- or distantly-related concepts. Words like: ‘terrain’, ‘environment’, ‘topography’, ‘country’, ‘place’, ‘location’, ‘situation’, ‘setting’, ‘site’, ‘surroundings’, ‘countryside’, and even ‘land’. Or visual words like ‘scenery’, ‘view’, ‘prospect’, ‘vista’, ‘panorama’, ‘outlook’, ‘background’.

In art, landscape is always primarily about culture, not nature. Though it may be counterintuitive to say it, ‘The Landscape’ hasn’t always been with us, waiting to be discovered by artists of the Renaissance. In fact, the word denotes a purely cultural construct, which could only arise alongside a humanist, rationalist, scientific and increasingly secular attitude to the world – and ‘modern’ modes of economic, social and political activity. It reflects a new paradigm in the relationship of humans (both individually and collectively) to the world outside them – which began quite specifically in Western European societies of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Altdorfer, Albrecht. Landscape with a footbridge, c. 1518-20. Oil on panel.

“The first ‘pure landscape'”?!

The word describes both a genre (‘landscape’) and its instantiation (‘a landscape’). On closer examination, some connotations can be discerned. Firstly, selectivity. Conventionally, a landscape artwork isn’t just a randomly captured view of the natural world. Rather, it has been framed, interpreted and executed (in the attempt) to generate aesthetic pleasure in the viewer. This may be mediated by way of a pleasing visual composition of elements, through symmetry, repetition of forms, colour harmony or contrast.

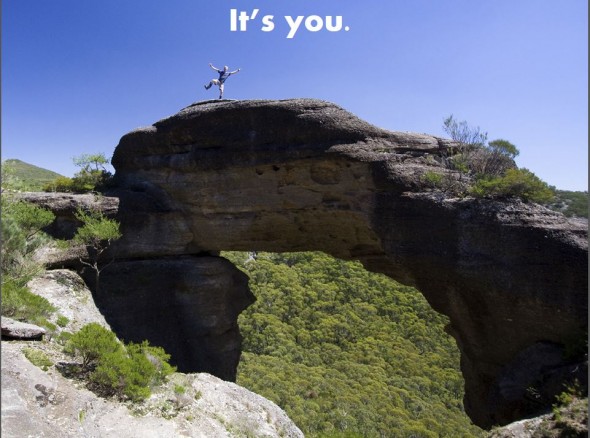

Secondly, there is the experience of vicarious travel, as the viewers project themselves into the depicted landscape. In such pictures, where the landscape is the subject rather than merely the setting, the viewer’s pleasure derives from immersion, from ‘virtual’ travel to a location perhaps more interesting than their current location, and the opportunity to (safely and conveniently) experience the distant and exotic.

Related to this is a third characteristic: the viewer’s emotional response. The viewer of a landscape artwork may experience feelings of tranquillity, harmony, absorption, excitement, awe, or even terror. In fact, landscapes are conventionally categorised according to their emotional impact on the viewer rather than their location or purely physical attributes. So we can talk of landscape categories of the Beautiful, the Picturesque, the Sublime, Pastoral, Heroic, Georgic etc.

The ‘scope’ of landscape is limited, as in many ways the experience of viewing landscape is quite superficial. Only the sense of sight is (directly) involved, and only the visible surfaces of landscape objects are (directly) perceived. Unlike ‘real’ experience of the world, there is rarely a sense of change or passing time. And the frame excludes all but a small window on the world, precluding full engagement with the land depicted.

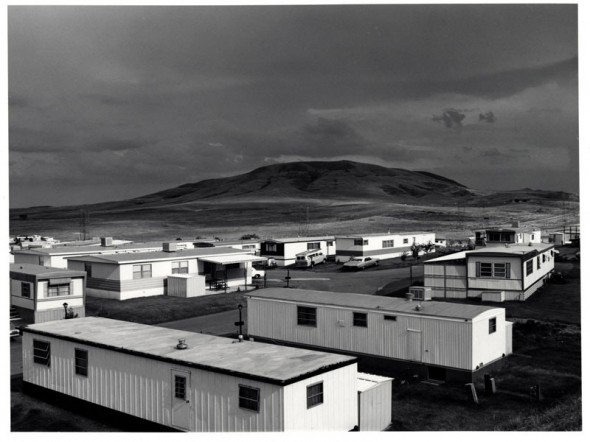

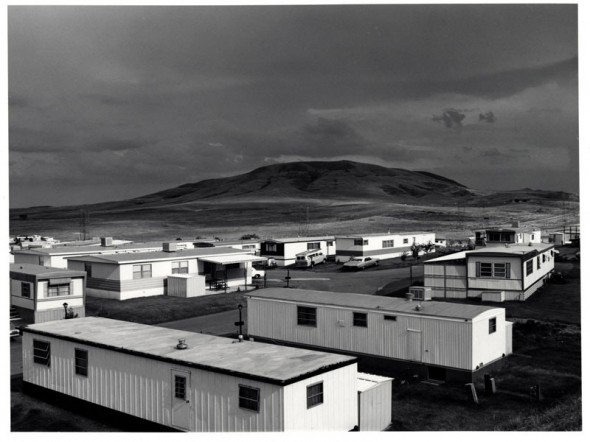

Adams, Robert. Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, Colorado. 1973.

From the ‘New Topographics’ exhibition

The notion of landscape in art has had many manifestations, and continues to shift (evolve?) with the cultures that generate it. Recent practice in ‘serious’ landscape art has often used the genre to comment on the social construction of our view of the external world, challenging assumptions underlying the traditional landscape image. The focus has shifted: from ‘pure landscape’ depictions or evocations of the ‘natural world’, to being explicitly about the manner in which human societies relate to, transform, contest or exploit that world. Human interventions in shaping the visual landscape are often dominant. Consequently, much of what we now readily accept as landscape would not be recognised as such by a 16th Century Dutch painter of landschap.