This post contains some thoughts on the depiction of ‘narrative’ in still photography, and was written as notes for my Private Thoughts in Public Places project.

Photographers have sought to portray narrative in their work since the inception of the art. It is obviously inherently more difficult to depict narrative in the still image than in a motion picture, as “a film unfolds in time and a painting [or photograph] does not”.

Several techniques are commonly employed to create or imply a sense of unfolding narrative in still images:

- Inclusion of objects in an image which indicate some antecedent or imminent event;

- Depiction of two or more human subjects in a way that indicates relationship between them (or evidence of a 2nd person who may be outside of the frame);

- Multiple related images presented as a chronologically ordered sequence;

- For a longer sequence of storytelling images, the conventional structural ‘rules’ of short story or video may be applied.

In recent years many photographers have explicitly refrained from presenting a complete or detailed narrative, instead implying narrative or presenting an ambiguous narrative for the viewer to interpret as they choose. Gregory Crewdson sees photography as related to the narrative forms of writing and video, but he is drawn to “the idea of creating a moment that’s frozen and mute, that perhaps ultimately asks more questions than it answers, proposes an open-ended and ambiguous narrative that allows the viewer to, in a sense, complete it”.

Untitled. Gregory Crewdson.

As Philip-Lorca diCorcia puts it: “the more specific the interpretation suggested by a picture, the less happy I am with it”. The subjects in his images do not engage directly with the camera, which enhances both the feeling of narrative and cinematic style of his images.

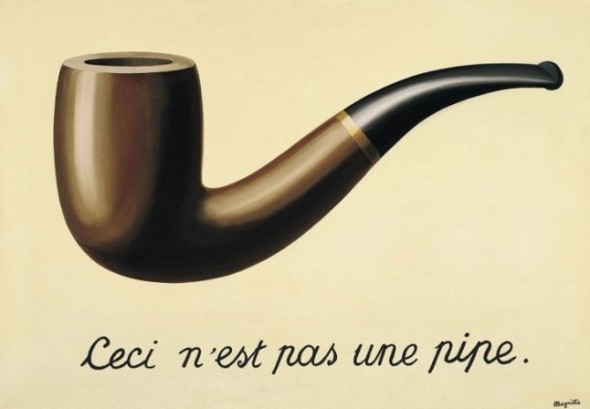

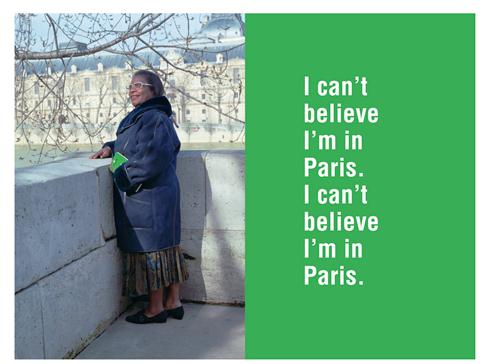

Untitled film still #96. Cindy Sherman

Similarly, in the work of Cindy Sherman (particularly in the Untitled film stills series) it is clear that one is viewing a scene from within a story, but without enough information to be certain of the story’s origin or outcome. The viewer is encouraged to develop their own narrative to explain the image.

This ‘less-is-more’ approach to exposition of narrative can engage the viewer more interactively with the image than if the story was fully resolved.

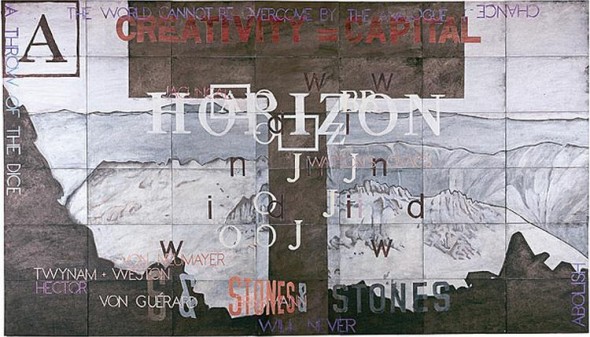

Self-portrait in a double-breasted suit with hare (2001). Sam Taylor-Wood

Sam Taylor-Wood goes further, constructing images (including large scale panoramas and videos) that take ambiguity to a level of possible incoherence. This is deliberate strategy: “you try to make associations between people and what they’re doing but you can’t necessarily find any narrative”. For the viewer, this can be unsettling… or unsatisfactory.

Mimic (1982). Jeff Wall

Jeff Wall has expressed doubt that still pictures can be narrative at all. “All they do is suggest what it might be like to experience the narrative. They don’t create one because they don’t have the ability. A narrative has to go in time and pictures can never do that.”

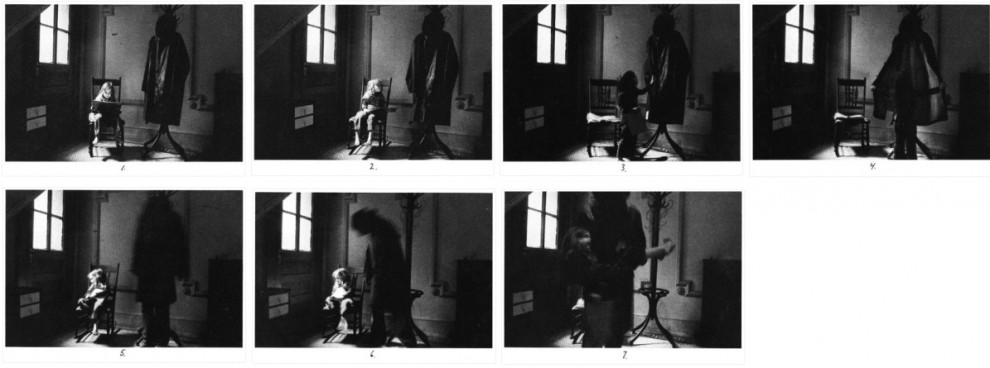

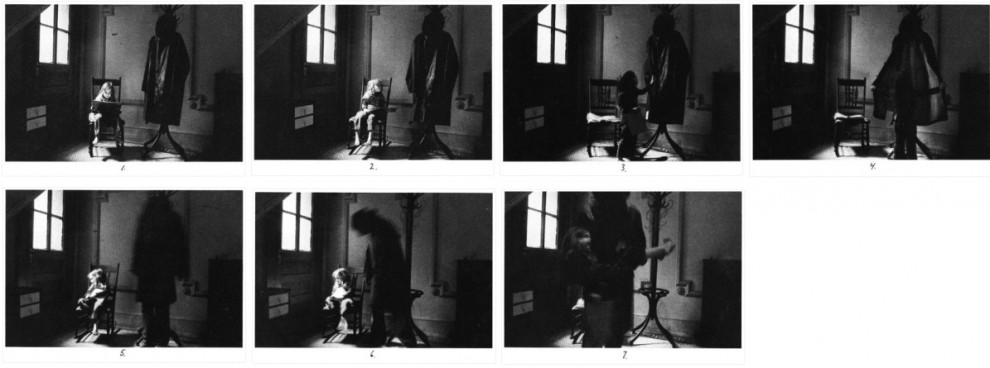

One approach to expression of narrative through still images is presenting a series of images in chronological sequence, as for example in many of the photographic series produced by Duane Michals.

Bogeyman (1973). Duane Michals

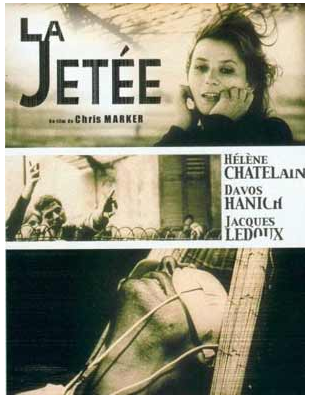

Chris Marker’s science fiction short film La Jetée (1962) tells a detailed story through still images. The film (and it was made as a film in those pre-digital days) consists almost entirely of several hundred photographs displayed in sequence, with an overlaid audio narration of the story. Despite being made up of photos, it imparts a quite detailed plot, shows the passage of time, has character development, and shows physical movement at key moments – such as in the final scene where the central character runs across the viewing platform at Orly Airport.

The experience of viewing La Jetée closely resembles the experience of narrative delivered through a motion picture. The story is thoroughly articulated (by way of the audio narration as much as the images), and the viewer is largely passive, and given little role in constructing the narrative.

Three decades later, La Jetée was released in a photo-book form, with all the same content (same set of images and text), but delivering a quite different experience to that of the film version. This is because the images are displayed at different sizes within varying page layouts, the reader can determine the pace of progression though the story, and is not limited to a strictly linear progression through the plot.

In my Private Thoughts in Public Places project, I have not sought to elaborate an entire story (although my initial intention had been to do so). The ‘plot’ is intended to be fairly clear at the beginning, with activities of the two protagonists presented as a logical sequence of simple events.

By the middle of the ‘story’, however, this thread dissolves and any semblance of explicit plot has gone. The pace slows, as their private thoughts take over and the urban environment becomes a dreamscape canvas onto which these thoughts are written. The intention is to progress from a narrative to contemplative mode.

[1] John Berger, Ways of seeing (London: BBC Books, 1972), 26.

[2] Gregory Crewdson, Dream of Life, 2nd ed. (Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, 2000), 17.

[3] Peter Galassi, Philip-Lorca diCorcia (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1995), 6.

[4] Bruce Ferguson, “Sam Taylor-Wood,” BOMB Magazine, no. Fall (1998).

[5] “Jeff Wall at Ruediger Schoettle Gallery [interview],” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwJUp_wxXfg.

[6] Chris Marker, La Jetée (Paris: Argos Films, 1963).

[7] ———, La Jetée: ciné-roman (New York: Zone Books, 1992).

![allen Annie Hall [still] (1979). Woody Allen. Spoken dialogue: “Photography’s interesting, ‘cause, you know, it’s a new art form, and a set of aesthetic criteria have not emerged yet.”](http://www.jokar.com.au/blog/wp-content/uploads/allen-310x150.jpg)