Durian!

Yes, durian! Loved by many as the Raja Buah (the ‘King of Fruit’), and reviled by others as stinky and disgusting. I’m a durian lover, and can’t comprehend those who aren’t. Perhaps it’s a genetically determined hypersensitivity?

There are around 30 species of durian, at least nine of which are considered to be edible. The durian genus is native to the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, with many growing wild here, and referred to as durian hutan (‘forest durian’).

LOTS of edible durian are produced in Kalimantan. Some of the best ones grow along the middle reaches of the Katingan River in Central Kalimantan, upstream from the town of Kasongan. Our favourite Dayak Ngaju village of Tewang Rangkang sits right in the middle of that zone. We were delighted to return there last month for a short stay during harvest season.

In Tewang Rangkang (as in almost all Dayak villages), the houses line up in a row along the riverbank. Behind the houses are areas where chickens and pigs are kept, and areas (often quite extensive) of fruit trees – especially durian. Further away (and across the river) are areas used for ladang dry rice cultivation.

There are no fences around the individual durian orchards, but everyone knows exactly who owns which trees. Each orchard is marked by a the presence of a pondok (hut), further asserting ownership. During harvest season (December – January) the pondoks are occupied day and night, with family members taking turns to stand guard over the orchard.

Pak Dahuk and Ibu Wanie have built a new pondok since we were there in 2015. It’s a solid structure, with an even more solid roof, so that there is no risk of getting beaned by a falling durian.

Not all pondoks are quite so grand. Some appear decidedly impermanent.

And others, like Pak Etiu’s pondok, are somewhere in between.

The stated intention of the pondoks is to protect the durian harvest from pilferers, because the fruit are quite valuable.

But actually there is actually little or no theft, and we think that the villagers just enjoy a special time of year when a large proportion of the population ‘camps out’ in the forest, cooking and eating and sleeping under the trees, and visiting their friends and neighbours residing in neighbouring pondoks.

And collecting the durian fruit as they fall to ground from the tall trees.

A mature durian fruit can weigh three kilos, and the rind is covered with characteristic hard sharp spikes. The word duri actually means ‘thorn’. A fruit falling tens of metres onto one’s head could potentially be fatal. Even the ground gets scarred by the impact of falling fruit.

I had one land a couple of metres away from me, with no warning but a colossal thump – and so I quickly retreated back under the shelter of the pondok roof.

Apart from collecting fruit and socialising, there’s work to do out in the pondok. Led by Ibu Wanie, everyone helps to prepare large quantities of dodol durian – for consumption, gifts and sale.

The durian flesh is removed from dozens of fresh fruit, and cooked up in a very large pan over a slow fire along with coconut milk, glutinous riceflour and gula aren (palm sugar derived from the aren palm). After hours of simmering and near-continuous stirring, a thick dark red-brown fudge-like paste is produced. It is delicious.

After production of dodol durian, and quite a bit of feasting along the way, there is a large a growing pile of discarded durian husks.

But it’s not just durian trees. The vegetation around many Dayak villages may at first glance appear to be secondary forest regrowth. But closer inspection reveals that almost every herb, shrub and tree has some productive value. So there are all sorts of fruit trees: bananas, papaya, langsat, mango, guava. And of course many coconut palms.

And rambutans – all in fruit at the same time as the durian.

And mangosteen.

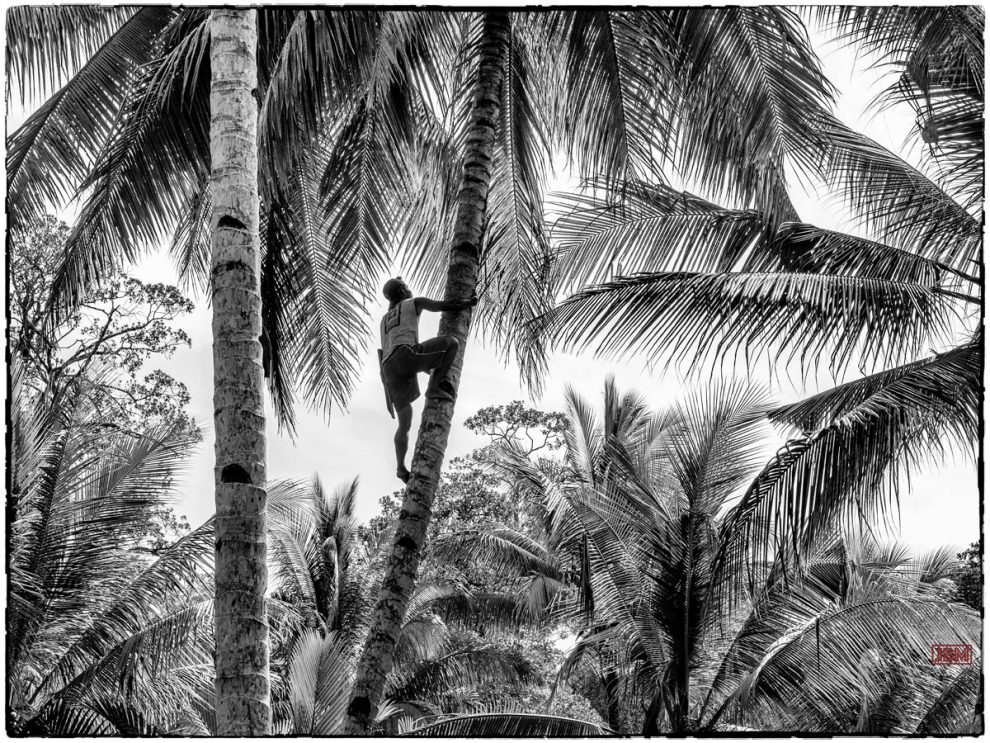

Pak Itiu shins up the mangosteen tree to collect fruit.

And meanwhile, back at the pondok, there’s time for a group portrait.

Desa Tewang Rangkang

Tewang Rangkang is a Dayak Ngaju village which stretches along a couple of bends of the Katingan River. It’s about an hour’s drive north of Kasongan in Central Kalimantan.

Since 2014 we have been frequent visitors. We’ve been privileged to stay there as guests of our wonderful Dayak Ngaju friends Mbak Lelie Liana, Pak Dahuk, Ibu Wanie Manur, Mbak Susi, Om Indra and Tante Hente – and their (very) extended families. Over those many visits we’ve witnessed manugal (communal rice planting) in 2014 and 2015, rice harvest, tiwah funeral ceremonies in 2014 and 2017, other family ceremonies – and durian harvest in 2015.