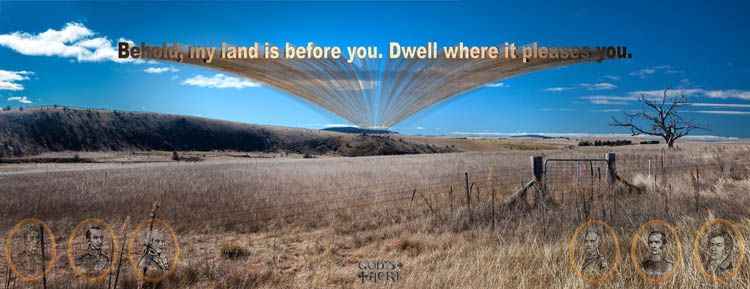

Doubtful (Click to view larger image)

The place names of the Snowy Mountains region have always seemed very special. For me at least, they have a romantic, even magical resonance in their sounds and the feelings that they evoke. Names like ‘Bogong’, ‘Monaro’, ‘Crackenback’, ‘Dead Horse Gap’, ‘Perisher’, ‘The Dargals’, ‘Pugilistic Creek’, ‘Dicky Cooper Bogong’, ‘Sue City’ – they conjure up images and stories of times past, and the various narratives of the Aboriginal peoples, the early European explorers and pastoralists, the workers of the Snowy Mountain Hydro Scheme and the skiers and hikers of modern times.

But the contemporary names, which are now fixed and codified by the Geographic Names Board (for NSW) conceal a history of confusion, change, and contention as European society struggled to impose a set of names onto the landscape which had managed to exist quite satisfactorily without labels on every locality and topographic feature.

There are many difficulties in establishing the names used by the Aboriginal peoples in the Snowy Mountains region (and similar problems in many other places too). The Indigenous naming system was not like that of the Europeans colonists.

There were more than 300 different language groups across the continent prior to European colonisation, and several groups that converged on the Snowy Mountains (especially for the summer Bogong moth migration), probably including speakers of Ngunawal, Ngarigo, Yuin, Walgalu, Bidawal and Jaithmathang languages. So one place may have had different names in different languages. One place (especially rivers) may have had several different names. A name may have been applied to a particular geographic feature as well as to the surrounding region, and some names may have had a secret or sacred dimension, and be known only to particular members of the group. Place names were often used to indicate the value or resources available from that location (‘Bogong’ is probably a good example of this). And further, land and mythology are inextricably related, and place names were often used to access the spirit and ancestor stories about places to which they are attached. (See the Our Languages website for further discussion of indigenous place names.)

When Europeans arrived in the region they generally sought to learn the local names for places from its inhabitants. This attempt was fraught with potential for error, however, for all of the reasons above. In the Monaro and Snowy Mountains regions, it soon became difficult due to the rapid decline in the indigenous population, and the disruption of their culture following the colonial settlers’ appropriation of their land. Also, Aboriginal words were often poorly transcribed into English text, and descriptions of places (e.g. ‘pretty’ or ‘resting place’) could be erroneously recorded as place names. The early European visitors themselves delighted in giving their own new names to places in the Snowy Mountains, blithely unaware of other names that may have been applied by earlier visitors.

A contest of names ensued, which can be also seen as a contest for dominance between the narratives and interests of the groups who supported different names. One result is that it can be quite difficult now to reconstruct the journeys of travellers to the region in the 1800s, as the place names they used may not have been recognised by anyone other than themselves! Our ‘modern’ “Mount Jagungal”, for example, has been variously referred to as ‘Bluff Hill’, ‘Big Bogong’, ‘Targil’, ‘Teangal’, ‘Jar-gan-gil’, ‘Corunal’ and ‘Coruncal’.

In my Doubtful image, I wanted to allude (perhaps somewhat obliquely) to this state of confusion and the contested history of place names in the region. “The Doubtful” is in fact the ‘official’ name of a real creek near Mt Jagungal. The Geographic Names Board describes it as “a watercourse about 19km long. It rises about 2 km NNW of North Bulls Peak and flows generally N into Tumut River.” For me it has extra significance as it runs adjacent to (my grandfather) Archibald Rial’s hut at Farm Ridge. Family legend has it that he (or his workers) panned the gold for my grandmother’s wedding ring from that creek.

Alan Andrews, in Kosciusko: the Mountain in History (O’Connor, Tabletop Press, 1991) suggests that its name might derive from the surveyor Thomas Townsend’s uncertainty in 1847 as to whether it flowed into the Tumut or Snowy River systems. (I haven’t looked too hard for a more definitive derivation of the name, as I rather like the uncertainty.)

In the Doubtful image, the letters of the word ‘Doubtful’ are not embedded in the landscape but placed on top of it. The letters are widely spaced, and in mixed case so as not to appear overly authoritative. The landscape itself was photographed with very shallow depth of field, to further accentuate the sense of uncertainty.