For some time, I’ve wanted to write about the mysterious masked characters known as bukung, babukung or sababuka (depending on which part of Central Kalimantan you are in – and who you talk to).

But I’ve put it off because (a) I didn’t have many photos and (b) I couldn’t get much definite information about them.

While I’m still unclear of much about their origin, meaning, history and purpose – I do at least now have few photos to share…! (And if you have corrections or clarifications to any of the text below – please let me know!)

We first encountered them at a Tiwah Massal (a Dayak secondary funeral, with a complex series of ceremonies running over days, weeks or months) at Tewang Rangas village (September 2015). That’s on the Katingan River, where they are known as bukung.

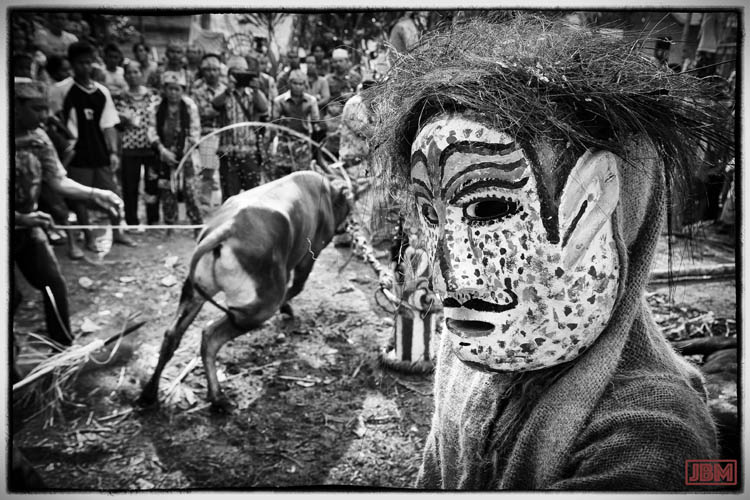

There were just three of them, but with their ghostly, impassive face masks (topeng), their silent demeanour, and rough-cut hessian clothing, they were a ghostly and powerful presence.

Over the days that we were there, they were (just about) constantly wandering around the ceremonial area of the village. Each one carried a split piece of bamboo (a selekap) in one hand, sometimes one in each hand, which they would raise and shake to make a loud rattling clacking sound.

We were told that the appearance and sound of the bukung is an effective way to scare off any malevolent spirits that may come into the village and seek to disrupt the ceremonies of the Tiwah. They certainly succeed in scaring small children of the village.

There are many taboos associated with Tiwah, including some about the bukung. The identity of each person behind the topeng (mask) is treated as a secret, and if anyone does know who they are, they are not permitted to address them by name.

At night, the bukung are not allowed to return to their own homes. If they need to sleep they must go and lie down somewhere in the forest.

So, at this Tiwah (but not at others we have attended..) our understanding is that they functioned as a sort-of spiritual security squad. At night time, when a fair proportion of the male population was under the influence of baram rice wine, they may also have performed some civil security role – though the bukung themselves also partook freely of the baram – and the baram drinkers were all remarkably good-natured.

At the Tiwah we attended in Bangkal village (March 2016), on the shores of Lake Sembuluh on the Seruyan River, they were also known as bukung. But, in number, appearance, activities and function they were very different indeed.

At Bangkal there must have been more than a hundred bukung, who arrived from down the road in successive groups over the two main days of the ceremonies. Each group was quite different, and they were welcomed by gongs and drums, and a curious and admiring crowd. Each contingent of bukung brought gifts, and was accompanied by a utility vehicle or small truck, loaded up with rice, drinking water, baram, chickens and pigs to be sacrificed and consumed during the ceremonies.

The Bukung Santiau were the first to arrive. These marvellous and towering figures were each around three metres tall, with clothing and a carved painted wooden headpiece mounted over a conical frame made from bamboo, rattan, raffia and cardboard. The man inside has to be quite strong just to carry the frame and keep it upright as he walks (and dances!) through the village.

This style of bukung (which we thought resembled the large ondel-ondel puppets of the Betawi people of Java) apparently originates in the upper reaches of the Seruyan River. However these ones were commissioned and made by local people of Bangkal village.

The Bukung Bukus Kambe – ghost bukung – wear large masks, some almost lifelike human in appearance, and others wildly stylised. Their most distinctive feature, though, is their ‘clothing’, which is made entirely out of grass, and leaves from banana palms and other plants. Like the Bukung Santiau, they came from Bangkal village.

The Bukung Garuda came from the village of Pondok Damar (on the road to Sampit from Bangkal).

The Bukung Raranga came to Bangkal from many villages. The figures represented the forms of various creatures, including fish, monkeys, bears, frogs and toads. Raranga is Dayak word meaning roh (Bahasa Indonesia) or ‘spirit’.

Some of the masks were large and quite elaborate, and would not have looked out of place at Carnival in Rio de Janeiro.

But not all of the bukung had elaborate masks or costumes. These ones above, although relatively simply attired, were some of the best and most impressive dancers. (Note that each of them carries a plastic bottle of baram rice-wine in his left hand!)

Many of the bukung arrived with cash gifts to help the host family with the considerable costs of the Tiwah (around 100 million Rupiah – or approximately AU$10,000). The blue headdress above, for example, has a million Rupiah pinned onto it.

At times there was a sizeable crowd of dancing bukung in the ceremonial area of the tiwah, in front of the house. There were even some ‘irregular’ bukung who joined in, such as the alien and the gorilla above…

Each of the arriving bukung was treated as an honoured guest (which they were). A small team of helpers from the host family would welcome them and provide them with baram rice wine, handfuls of cooked rice, cigarettes and sirih (betel).

However, since few of the bukung masks have operational mouths, some of the hospitality was a little wasted on them, and it could be a messy affair.

But human guests and hosts, such as our friend Pak Jaya (above right), also got to share in the baram and sirih – and managed to make rather better use of it.

The bukung bukus kambe, lined up in formation and clattering their poles of split bamboo in unison, were quite a formidable sight- sort of like a haka of forest ghost warriors.

One by one each bukung was summoned to approach the bamboo stairs up to the house and were admitted inside to where grandfather’s body was lying in state (as it had been for the previous four months).

The gongs and drums were located inside the house, and were really loud at times. The bukung danced for a while longer to where grandfather lay, and then lifted and (carefully and briefly) placed one foot on the coffin. Then the mask would come off, they became human again, and they sat down to share more baram, cigarettes and conversation.

Unlike the bukung of Tewang Rangas village, they made no attempt to conceal their identities, and they generally looked quite relieved to remove their hot and often heavy masks.

At Bangkal village (but not at the other Tiwahs), all the masks of the bukung were discarded after use, and many of them were carried to the cremation site where they were burnt along with the grandfather’s body. (The shirts of all the men who carried the coffin to the cremation site were also thrown into the fire, along with one very surprised chicken).

It was sad to see the topeng (masks) and the wooden heads of the bukung santiau, some of which were quite elaborate and beautiful, thrown into the flames of the funeral pyre.

Our third encounter was at a recent (April 2016) Tiwah, this time at Kuala Kurun on the Kahayan River up north of here in the district of Gunung Mas. But along the Kahayan we heard people calling them sababuka rather than bukung – (though this may have just been in reference to the mask, not the whole figure). Dressed in dried banana leaf clothing, and with grotesque white masks with big noses (like Europeans?) they looked like benign monsters.

An important part of the Tiwah is known as the laluhan, when honoured guests from another village arrive on board a massive bamboo raft (rakit), gloriously decked out with multicoloured flags. About a dozen sababuka accompanied the rakit on board a number of kelotok longboats, dancing (as best they could on a very narrow canoe) and waving their swords around.

They looked quite stunning and other-worldly in the relatively early morning light.

Our understanding is that these sababuka are the embodiment of spirits who could be malicious or dangerous, but who have chosen to support the Tiwah, and its function of helping the souls of the deceased on their difficult journey through the Upper World to the ‘Prosperous Village’ (Lewu Tatau) of Dayak heaven.